A New Book Tells the Story of the Man Who Paved the Way for the Big Data Revolution

“A fascinating book!”

–Dillard’s Chairman and CEO Bill Dillard

“An enjoyable and engaging book written by a man

it is a privilege to know and work with.”

–Madison Murphy, chairman of Murphy USA

“It’s a story as American as apple pie.”

–Gen. (ret.) Wesley K. Clark, former NATO

Supreme Allied Commander

“The book’s prologue, in fact, opens on Sept. 14,

2001, and Morgan describes the building of The

Bad Guys Database. Passages like the following

make the book a page-turner: ‘Data mining is the

new gold rush, and we were there at first strike,

dragging with us all our human frailties and

foibles. In this book’s cast of characters you’ll find

ambition, arrogance, jealousy, pride, fear,

recklessness, anger, lust, viciousness, greed,

revenge, betrayal—and then some.’ There’s

more—oh, so much more—to the memoir,

including juicy bits about a fierce proxy battle with

Acxiom’s largest institutional shareholder”

–ArkansasBusiness.com

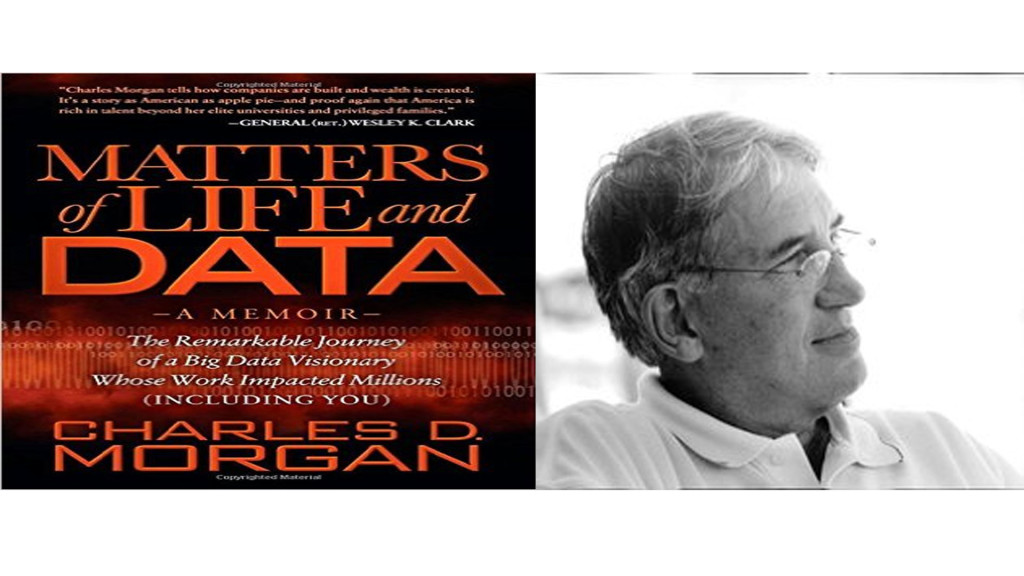

Corporations, marketers, and governments are exploring the practical and legal limits of collecting and utilizing Big Data. One man began thinking about its value decades before anyone else, and he’s revealing his professional insights, personal experiences, and career triumphs in a new book, Matters of Life and Data: The Remarkable Journey of a Big Data Visionary Whose Work Impacted Millions –Including You (Morgan James, ISBN: 978-1-63047-467-6; Cloth; 320 pages; $24.95; July 6, 2015).

“The man who opened your lives to Big Data finally bares his own,” reads the introduction to this most stirring memoir. Indeed, he has much to share, as Morgan, 72, should know a few things about Big Data. The company he helped grow into a technology and marketing powerhouse, Acxiom, is a world leader in data gathering and its accompanying technology, and has collected over 1,500 separate pieces of information on some half a billion people around the globe.

His book recounts and celebrates a journey from his modest upbringing in a small town on the Arkansas River to his role as one of America’s all-time Big Data visionaries. During his 36-year tenure, Morgan grew a small data processing firm of 25 employees into a global juggernaut by becoming one of the largest aggregators of data and consumer information in the world. He transformed the small data processing company into a publicly held, $1.4 billion corporation with 7,000 employees and offices throughout the world.

Other topics covered in his book include insights from his current experiences as a serial entrepreneur – founding, leading, and serving his many ventures that include PrivacyStar, a technology solution to support consumer privacy in mobile, and Querencia, a luxury golf and residential community in Los Cabos, consistently named a top course in Mexico by Golf Digest.

Morgan is available to discuss the challenges of Big Data, including:

* How he mined Big Data to assist the FBI in a post-9/11 terrorist investigation

* How to strike a balance between a company’s needs and a consumer’s interests

* How to maximize value from data

* How to serve the government’s security needs while protecting a citizen’s privacy

* How to integrate Big Data technology with existing infrastructure at a company

* Ways to balance and address risk and governance issues

He also addresses some unique approaches taken at Acxiom, including how he:

* Tore down 13 layers of organizational management and did away with all job titles

* Helped the company avert bankruptcy by imposing massive temporary pay cuts

* Made Acxiom the first technology company to create the position of Chief Privacy Officer (after a

breach with Citibank)Led the database giant’s transformation into a digital marketing company

His book explains how he was inspired by his hardware-store-owning great-grandfather, and how he learned about running a business when he worked as a boy at his parents’ motel after school and on weekends. After getting his degree in mechanical engineering in 1966, his first job was at the Little Rock office of IBM, where he quickly became the state’s top systems engineer.

Morgan also shares scores of leadership tips, insights on handling growth, managing a corporate culture that continually expands through acquisitions, and stories of how his growing database company once ran the most advanced data mining system of its time. Its then-revolutionary List Order Fulfillment System (LOFS) helped manage the subscription mailing lists of Fortune and Life magazines and helped 14 of the 15 largest credit card companies reach out to consumers to sign them up for millions of credit cards. In 1994, the Sales & Marketing Executives Association named Morgan Manager of the Year. In 1996, Fortune named Acxiom one of the “100 Best Companies To Work For,” and in the late 1990s Working Woman named it one of the nation’s “Top 100 Companies.”

Morgan took the company public by age 40 and oversaw significant growth. Annual revenue grew from 7 million to 90 million dollars from 1982-1992 and then it grew to more than a billion by the end of the 1990s. Morgan retired from the firm in 2007 after a buyout deal with Value Act and another private equity firm fell through.

His book also speaks with surprising candor about his messy divorce—so messy that Oprah invited him to discuss it on her show (he declined). After his divorce was final, he married his present wife of nearly two decades, a former Miss Arkansas USA. He also discusses his other love—racing cars. Though he crashed and landed in a trauma unit more than once, he was willing to pay the price to get the rush of going over 200 miles per hour. He also won 19 races, including the 12 Hours of Sebring and the 24 Hours of Daytona.

Though Morgan candidly admits to “wrestling with questions of leadership” and “making bad decisions,” he brings forth an honest look at a legendary career, a successful company, and a passionate private life.

Charles D. Morgan

Biography

Charles D. Morgan is the CEO of First Orion Corp., a private company that developed and markets PrivacyStar, an application that helps protect mobile phone users’ privacy. He is also an equity owner of Bridgehampton Capital Management LLC, for which he also serves as chairman of its advisory board and co-manager of investments.

His memoir, Matters of Life and Data: The Remarkable Journey of a Big Data Visionary Whose Work Impacted Millions (Including You) will be published by Morgan James (July 2015).

Morgan has extensive experience managing and investing in private and public companies, including Acxiom Corporation, the information services company where he served as CEO from 1972 to 2008, and that he helped grow from an early-stage company to an international corporation generating $1.4 billion in annual revenue. The New York Times cited Acxiom as “a top performer in the late 1990s” and both Fortune and Working Mom said it was “one of the best places to work” at that time.

Morgan has served on the board and in various leadership roles with the Direct Marketing Association (DMA), including as its board chairman in 2001. Prior to joining the company that became Acxiom, Morgan was employed by IBM as a systems engineer, and he holds a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Arkansas.

He is on the board of INUVO, Inc., a public company focused on simplifying performance-based advertising. He also serves as a member—and is the past chairman of the board of trustees—of Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas. Morgan is also chairman of the board of Querencia, a private golf development and golf course in Cabo San Lucas, Mexico.

A lifelong lover of auto racing, Morgan has participated on both the amateur and professional circuits. He has built and driven his own race car, competed against the best in the world, and has driven to 19 professional victories. He and his wife, Susie, a former Miss Arkansas USA, live in Little Rock, Arkansas. They have three children and seven grandchildren.

For more information, please consult http://www.mattersoflifeanddata.com/

Charles D. Morgan

Q & A

Matters of Life and Data

1. How can we protect the privacy of individuals but still allow companies to benefit from the use of Big Data? Big Data has the potential to do a great deal of good in our world today and for many years to come. On the other hand, Big Data will create a lot privacy issues. Today, much more data is being recorded about each of us than you might imagine. In February 2015, for example, Samsung admitted that their new TVs will be collecting data about the people who watch them. That data will include voice data (what you say about what you are watching), picture data (your expressions as you watch), and viewing data. Samsung of course claims that this data will only be used to improve the quality of the overall experience of using their product. Do I believe them? I don’t doubt that this is what they intended these data-collection TVs to do, but it sure doesn’t take much imagination to see a great potential for misuse of such data. We will never be able to write enough laws to totally solve this problem. We cannot stop companies from using data that improves the quality of products and services. However, we must somehow protect ourselves from misuse. At Acxiom, our motto was “consumer privacy is a state of mind.” It didn’t matter if something was legal; the question should be posed, “Is this right? Is this the way we would want to have our data collected and used?” Companies have to have education programs for their employees and create that state of mind—that the security of people’s personal data is important to our whole society.

2. If you were to advise an entrepreneur looking to launch a company today, what three things would you share? By their very nature most entrepreneurs are very optimistic people. When they have an idea, they believe that it can be developed and made commercial with much less effort than it generally takes. My executive summary is this: It’s going to be a lot harder and take a lot longer than they could ever imagine. First, entrepreneurs must be sure that the product they have is real and the plan they have is real. By that, I mean that the product and plan can be converted into a commercial success. It’s very easy for people to fall in love with their own ideas and to want to ignore all the pitfalls and the downsides. A product plan and a marketing plan are essential to test the basics of whether this thing that they’ve come up with is even practical. Marketing is where most plans fail to be realistic. For example, be sure the cost of acquiring new customers is real. Second, I would say that when you’ve convinced yourself that this new idea of yours has potential, then try to enlist the support of others. No person by himself is going to be successful developing an entrepreneurial idea. It takes a lot of people, and all those people have got to believe strongly in the concept that is being developed. If enlisting others is impossible—or even very difficult—then examine once again the practicality of the whole business idea. Finally, and most importantly, the developer has to be sure that he or she has access to adequate capital to develop the business. All too often people think they’ll be able to get more money after they show how cool their idea is. Most often that additional money is never found and the team just wasted a lot of their own money and some of their friends’ money. Best rule: Line up two times the money you need to get to phase 1—and you will be lucky to squeak by with that much.

3. You say that Acxiom Corporation, a world leader in data gathering and its accompanying technology, has obtained some 1,500 separate pieces of information on over a half-billion people worldwide. How do we make sure the information is not used wrongfully? I had great concerns about the possibility of data misuse at Acxiom. We had literally hundreds of thousands of data files with extraordinary amounts of in-depth information about everyone who lived in the United States and many in Europe. I developed a philosophy that we could not create enough rules at Acxiom to solve the problem. Eventually I came to believe that creating an atmosphere and culture of data protection was the best answer. We chose to educate our people and to create a simple set of rules. For example, the “do right rule” taught our employees to think about the data that they cared for as data about people just like themselves—in fact, it could even include their own family members. So treat that data like you would want your own data to be treated. Of course there were more complex rules that applied in all of our data practices. There were—and still are—laws that protect people’s credit data. Credit data could only be used for preapproved credit offers and not for other kinds of marketing. To help oversee all this process of education and oversight with our employees and our customers, in 1991 I appointed a chief privacy officer. Jennifer Barrett became the first chief privacy officer in the United States, and today she still holds that position at Acxiom. Jennifer has become a global leader in marketing data use and data protection.

4. You helped build your own race car, having won numerous races including the 24 Hours of Daytona and the 12 Hours of Sebring. What kind of rush did you get going 150-160 miles per hour? Did you ever crash? At the ripe old age of 58, I was driving at Daytona in my last event before retiring from professional racing. I was in a Ferrari 333 SP in the middle of the night, and on the front straight I was regularly hitting the rev limiter—a device designed to restrict the maximum speed of an engine. I came into the pits and asked the engineer how fast my car was going when it hit the rev limiter. His answer was about 205 miles an hour. Admittedly, that was quite a rush, but most of the time as a race car driver you’re totally unaware of the speed at which you’re traveling. Your goal is to go as fast as you can without crashing or tearing up the car. In my heart I’m a geek and an engineer. I liked designing and building cars as much as I liked driving. My son and I drove several races together, including a major race in Canada that we won in a car I designed. That was as big a rush as going 200+ miles an hour at Daytona. Other than the fact that I occasionally went 200 miles an hour, I was a pretty cautious driver. If I crashed I had to pay for it, and we might not have enough parts to fix the car at the racetrack, ending the weekend for me. As a result, I didn’t have all that many crashes. But you can’t drive race cars for 25 or 30 years and not be involved in accidents. I had my share of driver errors and mechanical failures that resulted in some pretty serious wrecks. I hit the guardrail at Watkins Glen racetrack doing nearly 150 miles an hour. Earlier in my career I hit the wall at Road Atlanta and was helicoptered off to the trauma center. Fortunately, in neither case was I seriously hurt. The Road Atlanta accident had an amusing sidebar. I was in the trauma center all by myself, plugged into all sorts of stuff. The door to the trauma center kept opening and closing with hospital personnel sticking their heads in the door—only to quickly turn around and leave. Finally, I heard one complain loudly, “That’s not Paul Newman.” Paul Newman was racing at road Atlanta and the rumor had gone around the hospital that he was in the trauma center, but to the staff’s disappointment they found only me.

5. You’ve also raced motorcycles and flown jets. How does the adventurous side link to your business life? Some amount of measured risk-taking occurs when you race cars, drive motorcycles, and fly jets. By the same token, most successful entrepreneurs are by their very nature risk-takers. They would never have started that business or risked their family fortune without being able to stand a certain amount of risk. Also in business, you have to believe that you’re going to be successful and overcome those risks. By the same token, you don’t enter a race and think, Oh goodness, I might crash and hurt myself. I always wanted to manage my risk to the greatest degree possible. I’ve never raced so hard that it was win or die, and I’ve never bet everything on a business venture. Well, almost never.

6. You are the CEO of your latest tech venture, PrivacyStar. It’s been seven years since you stepped down as chairman and CEO of Acxiom. What did you still find rewarding—and challenging—in trying to grow another company? Creating and building a small company is a lot more fun than trying to manage a much larger company. Sometimes at Acxiom I felt like I was trying to herd cats as I provided leadership on a multitude of fronts. Many parts of the public company CEO’s job are really not very enjoyable. You have to deal with lawyers and boards as well as many other distractions, like unfriendly press. I always wanted to spend as much time as possible on new product development and leadership activities at Acxiom. Down deep in my heart, I felt like life was being sucked out of me by activities that were beyond my control. There were things I just had to do and couldn’t get out of but I sure didn’t like them much. I felt like I didn’t have enough time to do the job that would contribute most to the growth and success of Acxiom. In a small company like PrivacyStar, I am able to spend much more of my time working on things like new product creation and development. We are doing things that no one else is doing in the mobile space. We built ourselves from a big money loser to a profitable company. That is fun. There’s still a lot of work and worry, but the overall satisfaction level is a lot higher for me when I feel more in control of my destiny and doing things that I enjoy. If we miss a quarter at PrivacyStar, it’s only us who are disappointed, and there are no newspaper headlines.

7. While working at your first job at IBM as a systems engineer, you were called back just a few days into your honeymoon due to an urgent office matter. Was this the beginning of your career consuming your life? I was shocked, only a few days into my honeymoon, to receive a call from my new boss who said, “Charles, we need you back in the office.” He knew where I was because he had come to the wedding in Fort Smith, all the way from Little Rock. Without too much protest, my wife of just a few days agreed that we could go back to Little Rock and I could start work. My first job at IBM was to get involved in a troubled installation of a computer on which I’d had absolutely no training. I had to teach myself what I needed to know in order to help get these problems resolved. I did that in a number of other situations that seemed to follow one after another. I was working all day and studying many nights to try to figure out how to achieve a good result for one customer or another. That was the story of my early experience with IBM. I was either working at a customer’s office—sometimes all night—or off on a trip to learn about some new machine or learn some new skills. In those early days, IBM sent new people off to school in the first two years for about 20 percent of the year. During that time, I recall having at least two one-week schools, two four-week schools, one six-week school, and one seven-week school. Those first two years were a compressed learning experience. And my job was far from purely technical. Besides learning about programming and design, I became very involved in the selling process, as well as in the organizational process of being sure customers were properly prepared for their new computers. The downside of all this is that I became quite one-dimensional. It was all work and I had little time for family or other activities. I was very successful at my job but not nearly as successful at home and with my kids.

8. Early on your company was in debt and couldn’t make payroll. You asked people to cut their pay in half for a period of time in exchange for paying them a more once you got past the dark period. How did that turn out? We got to a point in 1976 when we were losing money and were in danger of not being able to make payroll. Our principal owners, the Wards of school bus fame, were in terrible financial shape and they had no ability to help us out. There was no one to fire and no way to cut expenses that I could see. So I came up with the crazy idea that if we could make our payroll a third smaller, we could survive. All we had to do was to get the top six most highly paid people, including myself, to take a 50 percent pay cut. I can’t imagine going to a management team today with such a scheme. We were working on some new very promising opportunities that would make the company profitable if we successfully completed them. I told everyone that they would get two dollars back for every dollar of pay they gave up, should we succeed. I must’ve been very convincing because they bought it and no one left. And not only did they double their money, but through this crisis we also developed increased levels of trust and a stronger bond within the top leadership team.

9. To what do you attribute your success in becoming a dominant force in the market database world? Several things. We had a number of principles guiding our business strategy and execution. One was to hire outstanding people—we recruited intensely at area colleges and universities and were able to attract the best and brightest young graduates. Another was to provide world-class service to our customers, which helped us both acquire and keep customers. Take Citibank—it became a customer in 1983 and is still a major customer of Acxiom’s today. From our earliest days we also put a premium on designing and creating leading edge software, and that gave us a leg up in the marketplace. In the mid-1970’s, for example, we created a revolutionary way to manage and deliver mailing lists for the Direct Marketing industry. The List Order Fulfillment System (LOFS) was faster, better, and cheaper than existing mostly manual systems were at the time; more importantly, LOFS was more accurate. Another game-changer was called AbiliTec, introduced around the year 2000. AbiliTec made large-scale name and address data far more accurate than ever before, and to this day it remains a key component of Acxiom’s technology arsenal. We created a business culture and an organizational strategy that helped us be more nimble—and more efficient—than most other companies our size. We instituted formal initiatives that emphasized leadership, and we provided our people with training in the qualities of effective leaders. We also did some pretty radical things, such as doing away with corporate titles. When I gave up the title of CEO and introduced myself simply as Acxiom’s “Company Leader,” I got more than a few puzzled stares. All of these concepts worked together to create an effective leadership team and to achieve solid results for our customers, over many years. But satisfaction wasn’t limited to customers—employees liked the atmosphere at Acxiom as well, and the company is full of people who have stayed for decades.

10. You struggled with time management. What advice do you have for those consumed by any distractions and desires but who seek to manage and grow a company? Being leader of a large organization is a study in frustration for the top executive. Much of the CEO’s time is commanded by the corporation and the duties of his position. Boards of directors, top customers, and the company’s leadership team can eat up a significant number of hours in a CEO’s day. Over my 35-year career at Acxiom, I struggled to learn to be more effective. In my early years, I thought I had to be involved, at least to some degree, in virtually everything. But I knew I wasn’t very good at things like accounting and administrative work, and in time I figured out that there were people who could do these things better. At first I was worried that they would screw it up and maybe I should stay more involved. And of course I was right—they did screw up many times. Finally, though, I figured out that if I delegated things to the right people and showed them that I trusted them even though they occasionally failed, they would end up doing a better job overall than I could in those areas. That was one half of the equation—to shed the tasks where I could provide limited value to the corporation. The other half was to develop techniques to allow me to spend more time on the activities in which I could create the most value, such as research and development.

11. What challenges did you need to overcome as a leader during the number of acquisitions and mergers your company participated in? Acquisitions are always very difficult. When you finally get the deal done, which often takes months or even years, the work is just beginning. Every situation is different and none of them are without their challenges. A small one can be every bit as hard as a big one. Technology integration, cultural differences, and distance are all barriers to the smooth successful merging of two companies. I really don’t think we ever got it truly right. I know that my being involved always helped. Leaving small deals to others was often a bad idea. If a deal is worth doing at all, the CEO should take an active role to be sure that the integration of the two companies is accomplished successfully. With smaller acquisitions, probably the biggest challenge was forcing myself to spend enough time with the management teams in these acquired companies to make them feel part of Acxiom as a whole. The leaders of acquired companies are always nervous in the best of cases. They’re not sure how they’re going to be accepted by their new bosses. They’re not sure what to expect or even how to act and respond to various things that they are told or asked to do. They need to know that they’re considered important and that they’re being listened to, especially by the top guy. I found I couldn’t just move on to the next deal until enough nurturing had gone on to ensure the long-term success of the previous acquisition. Some of that nurturing could only be done by me.

12. When you took your company public, what opportunities and dangers did this open up to you? When Acxiom went public in 1983, it opened up many new opportunities for us. For example, it helped give us the credibility that we needed to be able to deal with large banks and other companies on the East Coast. The money created by the initial offering gave us financial freedom and the ability to build buildings and buy computers that were critically needed. On the downside for me, I now had shareholders and a public company board looking over my shoulder. For the first 20 years of being public, that was never a terrible burden for me or for Acxiom senior leadership. But when Sarbanes-Oxley was passed and the new activism by shareholders began, our lives changed forever. Ever-increasing amounts of my time were devoted to board matters and dealing with shareholders. Sarbanes-Oxley wasted a tremendous amount of time for us and created a great deal of unnecessary expense.

13. What is your hiring and firing philosophy? My philosophy was very simple—hire the very best people you can find. That philosophy extended to the concept that you hire people when you can hire them, not necessarily when you need them. Over the years I’ve hired a number of people that I really didn’t have a job for at the time, but I knew they were so good that we would eventually find a great spot for them. They were generally some of the very best hires and made the biggest difference. Another key component of my hiring philosophy is that the senior leadership of any company needs to be very involved in the hiring process. Stars hire stars and duds hire duds. People doing the hiring have to be sure they’re putting good people in the right places. If you hire a superstar and put him or her in a dull and boring job, it usually ends in failure both for the company and the individual. Really good executives don’t like to fire people. If they hire a person, then they feel invested in him and want to see him succeed. When a hire isn’t succeeding, the tendency is to give that person numerous chances before resorting to the pink slip. And then the most common first statement after that firing is, “I should’ve fired him six months ago.” So my philosophy, often not followed by me, is that you know when it’s time for someone to move on. Take action, make your decision now, and realize it’s the best for the person and for you. Generally, you’re both in misery over it and know it’s coming, but you keep putting off the inevitable while hoping for a miracle. I have to admit I still do that. The upside of that is that you get a reputation for not making snap decisions about people who work for you. I guess it’s a good thing, and something that others respect you for, because you give a person multiple chances. At the same time, others will say, “Charles took too long to make that decision. I wish he was more decisive.”

14. At one point you eliminated everyone’s office title. How did that go? Eliminating titles came about at Acxiom through a complex set of circumstances. We had multitudes of titles just like most companies do today. We had directors, senior directors, and associate directors. We had levels within levels. Acxiom in the early 90’s was in desperate need of simplification. We had way too many bosses in our organization, and management structure was getting in the way of getting work done. It was just too hard and took too long to get anything accomplished. So we had to get rid of all those titles and layers of management. We redefined the company into three layers and replaced titles with roles and responsibilities for each person in the company. At the highest level you had me—I was now the “company leader.” Working for me were division leaders, and working for them were business unit leaders. That’s about as simple as you can get, but it left an awful lot of people that once had management titles, such as director, possibly with no title and nobody working for them. As you can imagine, that was not an easy transition. We lost a few people. All I can say is, we got through it and we became better for it. It gave us a great deal more flexibility to move people around in the company where they were needed. Things got done faster because there weren’t so many signatures required.

15. Is this a good time for database marketers? Now is the best time ever to be in database marketing. Today all successful marketing programs have a significant component built around the database and database marketing. Companies have access to much more data than ever and a myriad of wonderful tools to help them analyze that data and create successful programs. Still, it’s not magic. Database marketers have to be sure they have the right software for their needs and have to apply that software properly. That software must have access to accurate and relevant data for the kinds of problems being solved. The old adage still applies—garbage in, garbage out. Most people don’t realize that Acxiom’s true value-add during all those years was just getting the data right so that marketers had good data to work with. Many of our large customers employed some of the brightest database marketers and analytic specialists money could buy, but before Acxiom their results were spotty, at best, because of bad data. There’s a great deal of opportunity in today’s world for people who possess a good blend of the skills to get the data right and to apply the right tools to database marketing. As more specialized skills are required, a number of subspecialties have grown out of database marketing. For example, today you can have an entire career in just getting the data right. To that end, the University of Arkansas at Little Rock now offers a PhD in Data Quality.

16. Do you think the laws will change with technology as it relates to what information is gathered, shared, and used? Controlling the gathering and use of data has always been a complex problem to administer. The Internet is making this problem almost too big to comprehend. Certainly laws will have to be written and old laws amended to give basic protection to citizens of the world. On the one hand, people say, “I don’t want anyone using any data about me without my permission”—even as those same people post everything about their private lives on Facebook. On the other hand, companies say, “We’re going to protect the consumer and their information”—even as those same companies are putting cameras and listening devices in their TVs to collect information about viewing habits. Much of the data that companies collect for a specific reason is used to benefit consumers. The problem is that the quantity of the data that is being collected, by electronic devices and over the Internet, is growing exponentially today. Access to the data that companies collect is usually carefully protected, but not always. There have been a number of widely publicized situations in which well-respected companies have gotten in hot water for collecting and using data improperly. Additional laws are going to be complex to write, but are certainly needed to cover potential Big Data abuses. We do have examples of successful laws, such as the Fair Credit Reporting Act—25 years and counting, and that law is still serving us well. The best way to solve these problems is not to rush to a conclusion, but to get industry involved in making recommendations in new areas like the Internet. All I can say is, I’m glad I’m not a legislator or a lawyer, because I really don’t have great answers in this area.

Selected Excerpts

MATTERS of LIFE and DATA

A Honeymoon Cut Short

In jokes, the punch line usually comes on the third beat. So it was with our honeymoon. After a couple days, I got a phone call from my new boss. “I need you back here.” He said, even as I protested that I was on my honeymoon. He couldn’t be swayed. So after only three nights and two days of our planned weeklong vacation, Jane and I packed up and drove to our new apartment in Little Rock. The digital future beckoned.

Out Of Money

But as 1976 faded into 1977, I faced that the moment I had dreaded—had tried my best to stave off—was upon us: We would soon be out of money. Between payroll and the debt on the new computer, we would be in a negative cash-flow positon until we started generating income from the LOFS project. And there was nothing I could cut, nobody I could lay off—everyone was working 60 hours a week and we needed all their projects just to stay where we were. And I thought I’d known the meaning of the word dire before.

Then a brilliant, if radical, idea came to me—what if we executives take 50 percent salary cuts? That was the starting point; from there I worked out a formula for eventually making them whole again, and then some.

When the crew showed up for my impromptu meeting, first words were, “I see no choice but to cut everyone’s salary in half.” That, I promise you, is a real attention getter. Now there was silence in the room, all eyes and ears trained on me. I explained the circumstances that had brought me to that decision; then I went on to say that if this scheme kept the company afloat long enough for us to start making money, I would pay them back double what they had given up. In other words, if someone earned $3,000 a month and we cut that to $1,500, when this was over I would pay that person $3,000 for every $1,500 he had forfeited during the three- or four-month period I expect this belt-tightening to last.

Once the shock subsided, most of the executives went along with this emergency measure without serious qualms—they believed that much in the potential of LOFS. But no matter how fervent their faith in our project, it was their ability to survive for months on half salary that determined their response.

Racing Cars

In time I would learn that, for the most part, car racing isn’t quite as intense as motocross—even though you’re going much faster. Maybe it’s the nakedness, the physical vulnerability in motorcycle racing that greatly increases the intensity. But car racing is intense, and the zone transfers from the bike seat to the cockpit. When you’re successful in car racing, you’re almost totally unaware of the coming corner—and you’re not aware of the next one at all. You’re thinking, I’m going to go to there and brake. You’re just doing it from somewhere outside yourself. Instead of driving the car, you start feeling it: I feel the car slide. I feel the front end doing this. I feel the car getting looser. It’s like you’re aware of what the car’s doing, but not thinking about what you’re doing to drive it.

Big Banks, Big Data

And when Acxiom was getting started with the banks, most of the data was structured credit bureau data.

The big banks were marketing credit cards, which would become the basis of our great success. But it wouldn’t all happen overnight—in fact, it would take us some 15 years to give the banks everything they wanted to achieve. Because in the early ’80s, their voracious vision of the power of data surpassed all capabilities of the time. Computers had to get faster and cheaper. And even with our literally acres of computers, we had to embark on a long-range program of building the tools to reach their goals. From the start we had their end games as a concept, and we could slowly add to it. But along the way, we had to develop new techniques for managing unprecedented volumes of data, combining that data, updating that data, cleaning that data, maintaining that data. Those techniques and processes just didn’t exist on this scale on the early ’80s. So there was a huge amount to be invented to realize the big banks’ dream.

So accuracy of information is what it’s all about. And that’s the reason we had so much success with the banks—our whole business strategy was directed toward building computing systems, and software, and tools to allow our customers to create their models on these huge data assets. A model built on faulty data is junk—garbage in, garbage out. We had a computer strategy the banks needed, a software strategy they needed, and even our organizational strategy was directed toward working with Citibank, say, to find out exactly what they needed. For us, the bank work wasn’t just some add-on; it was what we did. We might not have been able to achieve the banks’ whole goal immediately, but even by the mid- to late 80s we could get to step one—then to step two, step three, and beyond—faster and with more accuracy than anyone else, and at lower cost. And we kept getting better and better. The banks tried occasionally to get other people to do it, so as to test us, but we were the guys who produced the best quality data—allowing them to create models that were highly predictive. So we dominated this industry. We dominated because, thanks to our unique computer strategy, we could process Big Data. Nobody else could.

Wiping Out All Corporate Titles

“We went from thirteen levels to three,” says Cindy. “And we eliminated all titles so that people didn’t have that competition thing going on.”

Ah, but humans will be humans—won’t we? “In hindsight,” says Cindy, “we should’ve done it a little differently. Because what we realized was that to some people when you lose your title, you lose your identity. So it rocked the organization. Thirty percent of the people were, ‘I don’t care.’ But seventy percent were, ‘Oh no!’ so we did replace it eventually, but not with traditional titles. We came back with you’re a team leader or you’re a business unit leader. We put leader in the title and that was intentional, because we wanted people to start leading. And we kind of adopted a motto—you manage things and you lead people. And if you can’t lead, then we’ll let you go manage things. But you can’t manage people. So that’s kind of how it started. That was a pretty big turning point, organizationally.

The Divorce Oprah Wanted To Televise

Being the former bookkeeper she was, Jane had kept every scrap of paper—every canceled check, every check register, every bank note, every IOU, every tax return, every ledger book—from the 60s on. So she and Steve had a veritable field day sifting through all those documents and building a case claiming that Jane was the power behind Acxiom’s success—that without her, I wouldn’t have happened. It was absurd, between 1991 and the end of that decade, our annual revenue would grow from $100 million to $1billion—and that was thanks to Jane?

“The Oprah show called to invite Dad on, “ says Carrie, “because the question in the legal culture in that period was, does staying home and raising children and taking care of a household entitle you to fifty percent of what in Dad’s case was then about $100 million? That’s what Steve saw at the time—lets go back and show what Jane’s contribution through the years was…besides the well-adjusted children!”

We were in no way contesting the Arkansas law that said she gets half of all community property. The question was, how do you define half? Half of what?

But what really made my attorneys nervous was that it looked she was trying to build a case that she could get more than half—because, as we interpreted what we of her argument, she came into this marriage with money, which she put in, but she never received stock, so I really ripped her off. That was the reason for all the depositions. I think it was a negotiating ploy mainly designed to inflict pain on me, because we certainly couldn’t ignore her claims that she should be getting more than half. Of course this ploy also created big legal bills.

King Of Big Data

Understand, even then Acxiom was starting to be known as “the Big Data guys.” We were getting talked about as this relatively low-profile company in Arkansas that had data on everybody—especially bank data. Among our clients were 14 of the 15 biggest credit card companies; seven of the top 10 auto manufacturers; and five of the top six retail banks. We analyzed consumer databases for such multinational companies as Microsoft, IBM, AT&T, and General Electric. So as the Internet increasingly became a vast, interlaced world of infinite promise, it naturally attracted opportunists the ways gold mines once attracted prospectors and con men. Data became the new currency. And if you were the kind of person who preferred to steal data rather than mine it yourself, where did you go? To the mother lode.

First Chief Privacy Officer

“The result was that, in 1991, I named Jennifer to the newly created post of Chief Privacy Officer. As a dedicated monitor ensuring the responsible use of all data in our possession, Jennifer Barrett broke new ground – she was the first such privacy officer of any company on the planet.

There was nothing at all altruistic about this appointment. I just knew that if marketers kept saying screw the public, one day we would have a big blow-up, and somebody would write a big privacy bill that would virtually shut down the industry. I decided to be proactive in confronting that possibility. I could already see that without a strong code of conduct, there were increasing opportunities for us to make the wrong decision and get into trouble. Jennifer’s new job was to keep us away from that.”

Holy Grail Of Big Data

“The Decade of the 2000s began brilliantly, with AbiliTec being touted as something akin to the data industry’s Holy Grail. In 2000, the year the dot-com bubble burst and sent the NASDAQ into a 30-percent plummet, Acxiom stock was up 65 percent. Clients using AbiliTec included such giants as Microsoft, Citicorp Credit Services, Mercedes-Benz USA, Palm Inc., Rodale Press, Bank One Services Corp., and American Express. In the first quarter of our2001 fiscal year (April 1, 2000 to March 31, 2001), earnings from AbiliTec amounted to an estimated $5 million; in the second quarter, the first time AbiliTec’s contribution was separated out from other earnings, the figure was $40 million. AbiliTec, I told the business media, “is changing the heart of Acxiom.”

The Beginning Of The Cloud

Today, the grid system we created would be called “cloud computing,” except ours was a private cloud, just for Acxiom’s use. We were the first to develop such a system, though there was this small company out west called Google that had a similar idea. Today when you Google something, you’re using that very secretive company’s acres and acres of linked computers.

About Acxiom

Acxiom, described by Forrester Research as one of the largest database marketing services and technology providers in the world, has annual revenues of $1.15 billion, representing more than 12% of the direct-marketing services sector’s $11 billion in estimated annual sales.

As the world’s largest processor of consumer data, Acxiom has identified 70 types of consumers with its segmentation product Personic X. In addition to collecting data on people, it helps marketers anticipate the needs of consumers, according to the documentary, The Persuaders.

Founded in 1969, the Little Rock, Arkansas-based marketing technology and services company trades publicly on Nasdaq (ACXM) and has offices in the United States (Chicago, New York City, Nashville, and Foster City, CA), Europe, Asia, and South America.

Acxiom offers marketing and information management services, including multichannel marketing, addressable advertising, and database management. Acxiom collects, analyzes, and parses customer and business information for clients, helping them to target advertising campaigns, score leads, and more.

Its client base in the United States consists primarily of companies in the financial services, insurance, information services, direct marketing, media, retail, consumer packaged goods, technology, automotive, healthcare, travel, and telecommunications industries, and the government sector.

In 2003, the Electronic Privacy Information Center filed a complaint before the Federal Trade Commission against Acxiom and JetBlue Airways, alleging the companies provided consumer information to Torch Concepts, a company hired by the United States Army “to determine how information from public and private records might be analyzed to help defend military bases from attack by terrorists and other adversaries.”

The FTC took no action against Acxiom.

In 2005 Acxiom was a nominee for the Big Brother Awards for Worst Corporate Invader for a tradition of data brokering.

On May 16, 2007, Acxiom agreed to be bought by leading investment firms Silver Lake Partners and ValueAct Capital in an all-cash deal valued at $3 billion, including the assumption of about $756 million of debt. On October 1, 2007, however, a press release announced that the takeover agreement was to be terminated and Charles Morgan would retire as Acxiom’s company leader upon the selection of a successor.

In 2013 Acxiom was among nine companies that the Federal Trade Commission is investigating to see how they collect and use consumer data.

September 11

by Charles D. Morgan

Tracking 9/11 terrorists was the farthest thing from my mind in the days after 9/11. It was one of our associates who came to me and said his team had found some of the 9/11 guys in Florida. This was right after the Justice Department had released the names of several of the terrorists, including that of Mohamed Atta. I insisted that we do more checking and was advised to call the FBI as soon as we were sure that the data could possibly be useful to the federal authorities. That started the process of chasing the bad guys, and it went on for several months.

We engaged with the international terror experts from the FBI, who came to Arkansas and worked out of our building. We assigned a team of some 30 of our people to build what we called “The Bad Guys Database” and to do analysis to see what we could figure out. I was quickly drawn in myself and became a key member of the team looking for any information about the terrorists that might be helpful to the authorities. Law enforcement was particularly interested in knowing who and where the terrorists’ associates were. We assembled a massive amount of data from our customers, from the credit bureaus, and from the federal authorities, and we secured permission to use this data through the use of subpoenas.

We then went on a massive manhunt that would completely consume me for several months. By 2001 we had developed a product called AbiliTec that was of tremendous help in this effort. It allowed us to link people with different names and even at different addresses so that we could comb through all this data and come up with accurate answers. We found all the terrorists who had lived in the U.S., as well as most of the places where they’d lived. We used that data to look for other possible conspirators in the locations where we knew the terrorists had lived. The apartment house in Florida and another building in New Jersey were places that many of the 9/11 conspirators had spent time. The FBI and the Justice Department told us that the work we did was tremendously beneficial to them. The whole experience was quite surreal for me. I could never have imagined that I would be working with the FBI to track down terrorists.

My only regret is that there’s still a lot of the 9/11 story that has never been told. For example, we located a Saudi who made trips in and out of the U.S. and always had a different destination for his stay here. All the while, he owned a house in the Washington DC area and a car that was registered to the same apartment house address in Florida where Mohamed Atta had lived for several years. I never found out what happened to this guy, but I’m quite sure he was in some way associated with them—most likely as one of their sources of funding.

Sadly, I also learned some things I wish I hadn’t. I discovered how woefully inadequate law enforcement’s systems and technology were at that time in this country. The FBI agents we worked with used extremely outdated equipment, if they used any equipment at all. Several of the international terrorist experts didn’t even know how to use a laptop computer in 2001. The laptops that several of them carried were more than five years old and weren’t compatible with any of the tools that we were using in our process. For example, I couldn’t even transfer spreadsheet data to their PCs. Much has changed since then, as the exploits of NSA demonstrate. But it was certainly an awakening for me at the time.

As a dedicated team of researchers pursued the suspects, we were able to learn a number of things about the way the government brought information together – mainly that there need to be significant advancements in that area.

So even as we hunted down the bad guys – we began thinking about techniques and strategies that, if implemented, could increase the probability of heading off terrorist attacks in the future. And we began formulating a plan to put our special capabilities on the table, in front of the people who needed to know such things. They could then decide whether or not they wanted to take advantage of them.

We made some phone calls and took some meetings. Tim Griffin, then an assistant U.S. Attorney and later a U.S. congressman from Arkansas, was very helpful. So was retired general Wesley Clark. Former President Bill Clinton came to town with Mack McLarty and spent an afternoon with is going over our findings. Our two U.S senators, Blanche Lincoln and Tim Hutchinson, had more of an in with the Bush Administration, and it was through him that we secured a private meeting with Vice-President Dick Cheney.

The meeting took place in the summer of 2002, in the Vice-President’s room at the United States Capitol. Our team included General Clark, Senator Hutchinson, Jerry Jones, and me. Cheney was accompanied by one of his senior aides. Cognizant of the Vice-president’s time, General Clark opened the meeting and got right to the point—that government agencies had embraced information technology over the past 30 years, but that as the individual agencies’ systems had grown, the ability to share this information within and between agencies had not grown with it.

Then General Clark introduced me. I made a short presentation explaining how government could solve its massive data integration problem in a manner that would be respectful of individual privacy rights, which was critically important and technologically feasible, and at a cost that we thought would be acceptable, all things considered. The Vice –President seemed to find this plan quite intriguing, and in fact the scheduled 20-minute meeting stretched on to nearly 45 minutes.

At the end of the presentation, we left the Vice-President with a 13-page single-spaced memo called “Data Integration in Government Agencies”—subtitled “Facilitating Information Sharing While Protecting Privacy and Agency Autonomy.”

Long before 9/11 we knew that data could get out of hand and be abused. And that was just reinforced for me recently as I began following the NSA’s secret exploits. Before 9/11 I never thought about using our data and technology for the purpose of national security. But those in the Justice Department and the FBI with whom we interacted were amazed at our capabilities—so much so that we had a chance to present our ideas to Vice President Cheney in Washington DC. In the aftermath of 9/11, we actually did decide to design systems using our technology to benefit national security. And we struggled mightily over how to put the right safeguards in place to keep from creating a monster.

I’m proud to say we came up with some very innovative ideas that required processes to protect people’s information and abuse. Sadly, very little of that seems to have been picked up by the NSA. We have an opportunity and a problem with Big Data. The opportunity is that many things can be done to potentially prevent another 9/11 from ever occurring. Data analysis tools today can scale to the point that every phone call into and out of this country can be monitored at some level.

It’s not hard to imagine some enterprising technologist saying, “Wouldn’t it be nice if we actually captured the conversations in some of the suspicious situations.” The problem is, one thing leads to another and another and another, and before you know it you’ve got a situation that further compromises our individual privacy. The NSA could build a capability for scanning every telephone communication from the United States to foreign countries, as well as all other electronic traffic, including email. But where does it stop? The answer is that it will never stop unless we put adequate controls in place through Congress.

Big Data

by Charles D. Morgan

Today we hear the term “Big Data” all around us, and I want to clarify what we’re talking about. The term Big Data generally refers to extremely large masses of unstructured and partially structured data that typically has some kind of content that can be used for marketing, or for business decision-making, or even—as you see in my book’s prologue –for tracking bad guys. Unstructured data only started becoming a factor in the late 1990’s, and very much so in the 2000s.

Back in ’70s and ’80s, though, we didn’t even use the term Big Data. We talked about “massive databases” or “huge data problems” or something like that. And even if we had used the term Big Data, it would’ve referred to something much different from what we mean by that term today. The data then was different both in body and form. First, there just wasn’t as much data available. We didn’t record what came into a call center, and business wasn’t done by email; it was done by phone and letter, and we didn’t have any way of translating it.

Big Data is just what it implies—a lot of data. Typically big data also indicates that the data may be both structured and unstructured and come from a multitude of sources. The growth and diversity of data in this country has increased in all dimensions due to the internet and the millions of devices around the world that collect data of all kinds. Big Data is useless without the ability to organize and glean information from it. In the past, we relied on traditional relational database architecture, which has turned out to be quite inadequate in the world of Big Data.

A multitude of new tools and capabilities are being developed by vendors around the world to effectively extract true information from Big Data assets. Some of these new companies, like Splunk, are very successful with their efforts. It concerns me personally that the quantity of data collection about our daily lives is increasing exponentially. With all this data collection going on, the opportunity for misuse is ever present.

Thanks partly to Edward Snowden and the NSA’s excesses, today’s ubiquitous Big Data is a concept that many people respond to with suspicion or outrage. It’s absolutely true that some holders of information misuse it – I’ve met some of those people over the years – and others don’t give a damn about your privacy – I’ve run across those types, too. But in telling my story, what I hope to show you is that data itself, as well as data gathering, is neither good nor bad; it’s how it’s used that matters.