The New York Times

Five years ago, a college freshman named Ian Burkhart dived into a wave at a beach off the Outer Banks in North Carolina and, in a freakish accident, broke his neck on the sandy floor, permanently losing the feeling in his hands and legs.

On Wednesday, doctors reported that Mr. Burkhart, 24, had regained control over his right hand and fingers, using technology that transmits his thoughts directly to his hand muscles and bypasses his spinal injury. The doctors’ study, published by the journal Nature, is the first account of limb reanimation, as it is known, in a person with quadriplegia.

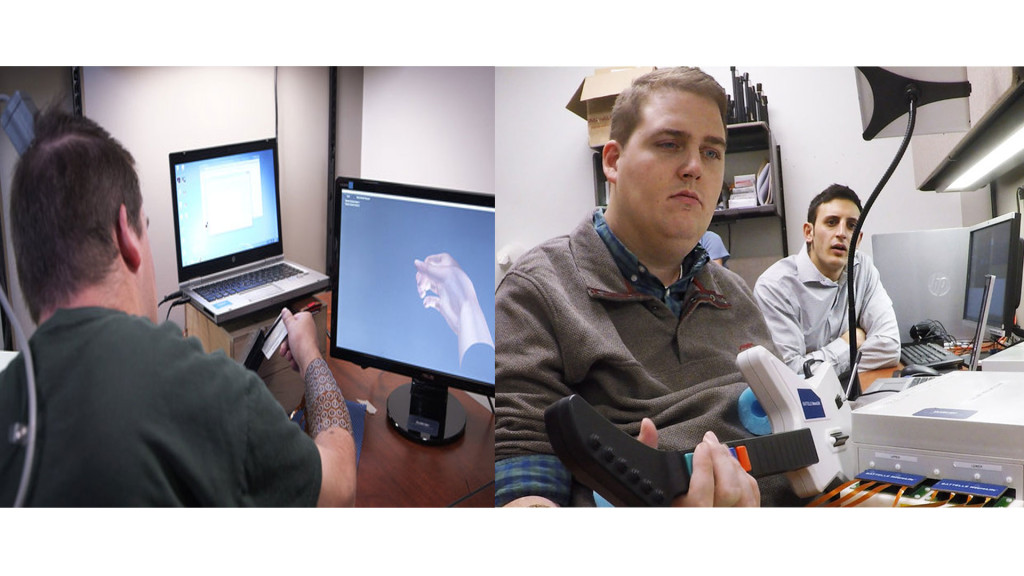

Doctors implanted a chip in Mr. Burkhart’s brain two years ago. Seated in a lab with the implant connected through a computer to a sleeve on his arm, he was able to learn by repetition and arduous practice to focus his thoughts to make his hand pour from a bottle, and to pick up a straw and stir. He was even able to play a guitar video game.

“It’s crazy because I had lost sensation in my hands, and I had to watch my hand to know whether I was squeezing or extending the fingers,” Mr. Burkhart, a business student who lives in Dublin, Ohio, said in an interview. His injury had left him paralyzed from the chest down; he still has some movement in his shoulders and biceps.

The new technology is not a cure for paralysis. Mr. Burkhart could use his hand only when connected to computers in the lab, and the researchers said there was much work to do before the system could provide significant mobile independence.

But the field of neural engineering is advancing quickly. Using brain implants, scientists can decode brain signals and match them to specific movements. Previously, people have learned to guide a cursor on a screen with their thoughts, monkeys have learned to skillfully use a robotic arm through neural signals and scientists have taught monkeys who were partly paralyzed to use an arm with a bypass system. This new study demonstrates that the bypass approach can restore critical skills to limbs no longer directly connected to the brain.

“It’s quite impressive what they’ve shown, this sequence of movements to pick up and pour something and pick up a stirrer — it’s an advance toward a goal we all have, to provide as much independence to these patients as possible,” said Rajesh Rao, the director of the Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering at the University of Washington.

After his injury, Mr. Burkhart underwent rehabilitation for months in Atlanta before continuing his care at Ohio State University, near his home. There, he told doctors that he would be willing to participate in experimental treatments.

“I was in the right place at the right time,” Mr. Burkhart said. “But it did mean I had to have brain surgery — surgery that I didn’t need.”

Some of his family members were against it. Adding the risks of surgery to what Mr. Burkhart had already been through was too much, given the uncertain payoff, they argued.

“There’s the recovery time, the putting the chip in, taking it out — and in the long run it doesn’t benefit Ian one iota,” said Doug Burkhart, his father. “He was doing it for the general good, to move the science along.”

Ian said he had none of those concerns. “I knew I was going to be taken care of, and something’s going to come along to help people like me eventually — so why not try.”

His father came around after consulting a high school friend who is a neurosurgeon. “Ian reminds me of my dad,” he said, “He’s one of those people, he’s driven, he’s decisive, once he makes a decision, he sees it through and doesn’t look back. He was going to do what he wanted to do.”

So in 2014, a surgical team at Ohio State operated. They used brain imaging to isolate the part of Mr. Burkhart’s brain that controls hand movements. The area is in what is known as the motor cortex, on the left side of his brain and just above the ear. During the surgery, the team did extensive testing on the exposed brain tissue to further narrow down the location.

“We spent an hour and half working to find the exact location,” said Dr. Ali Rezai, the surgeon and director of Ohio State’s Center for Neuromodulation. Dr. Rezai implanted a chip the size of an eraser head in the area. The chip holds 96 filament-like “microelectrodes” that record the firing of individual neurons.

After Mr. Burkhart healed from the surgery, the training began: multiple sessions in the lab each week, trying hand movements. The firing patterns were picked up by the chip and ran through a cable that was fixed to a port on the back of his skull and connected to a computer.

Scientists at Battelle Memorial Institute, a nonprofit organization in Columbus, Ohio, that develops medical devices, among other instruments, designed software to decode those firing patterns. And that code had to be recalibrated almost every session, said Herbert Bresler, a senior research leader at Battelle.

“The signal changes constantly as learning happens, and we had to adjust to those changes,” Dr. Bresler said. “The machine learned as Ian Burkhart learned.”

Dr. Bresler is the interim chief on the continuing project; the previous principal investigator, Chad Bouton, who has changed jobs, was the lead author. His co-authors include Dr. Rezai and a dozen others at Ohio State and Battelle.

Mr. Burkhart said the training was exhausting. An avatar on a computer screen cued him to try different types of movement. “I had to really, really concentrate, just to do these things I did without thinking before,” he said. “But it was like a sport; you work and work and it gradually gets easier.”

After several months, Mr. Burkhart no longer needed the avatar to imitate. “Watching him close his hand for the first time — I mean, it was a surreal moment,” Dr. Rezai said. “We all just looked at each other and thought, ‘O.K., the work is just starting.’”

After a year of training, Mr. Burkhart was able to pick up a bottle and pour the contents into a jar, and to pick up a straw and stir. The doctors, though delighted, said that more advances would be necessary to make the bypass system practical, affordable and less invasive, most likely through wireless technology. But the improvement was significant enough, at least in the lab, that rehabilitation specialists could reclassify Mr. Burkhart’s disability from a severe C5 function to a less severe C7 designation.

For now, the funding for the project, which includes money from Ohio State, Battelle and private donors, is set to run out this year — and with it, Mr. Burkhart’s experience of restored movement.

“That’s going to be difficult, because I’ve enjoyed it so much,” Mr. Burkhart said. “If I could take the thing home, it would give me so much more independence. Now, I’ve got to rely on someone else for so many things, like getting dressed, brushing my teeth — all that. I just want other people to hear about this and know that there’s hope. Something will come around that makes living with this injury better.”