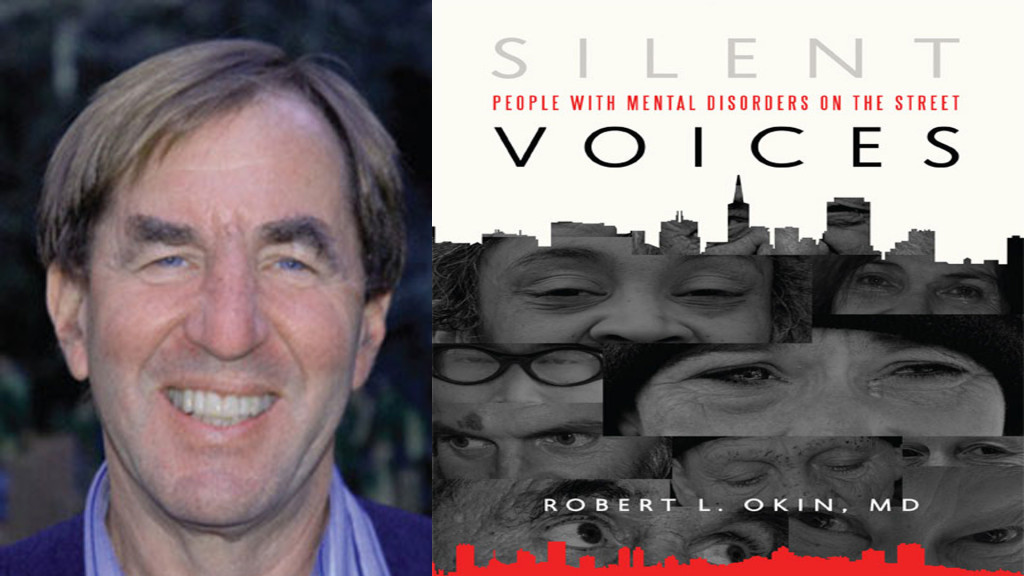

Psychiatrist and Human Rights Activist Dr. Robert Okin Wants All Americans to

See the Faces and Listen to the Stories of Our Society’s Most Overlooked Outcasts:

The Mentally Ill and Homeless http://www.robertokinmd.com

From L.A. to Philly to Miami, they’re out there—pushing their carts, digging through garbage, sleeping on park benches, sometimes ranting about nonsense to no one. They often look and sound crazy, smell bad, and make us uneasy, so we avoid them. We know better intellectually, yet most of us shun people suffering from homelessness and mental illness because we view them as deeply flawed—somehow less human than the rest of us.

As part of his career devoted to the mentally disabled, Dr. Robert Okin decided to use a powerful artistic medium to advocate for these people. In SILENT VOICES: People with Mental Disorders on the Street (Golden Pine Press, October 2014), Dr. Okin invites all of us to get to know the people society treats like pariahs, people who, beneath their symptoms and rags, struggle with feelings and needs similar to those of the rest of us. He shares the striking and evocative photographs and stories—most often, in their own words—of more than 40 mentally ill people he met on the streets of San Francisco. “I wrote this book,” Dr. Okin reflects, “to contribute to making these people known as human beings.”

SILENT VOICES offers a glimpse of the dark pasts—marked by abuse, violation, tragedies, crime, drugs, and addiction—and everyday challenges of homeless men and women suffering from bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and other serious mental disabilities.

Based on his interviews, research, and decades of professional experience, Dr. Okin discusses:

Staggering facts on how the mentally ill are neglected, mistreated, and discriminated against. In America today, over 200,000 people with mental disorders are abandoned in the streets and another 250,000 are locked up in jails and prisons.

Measures needed to reduce the widespread, escalating problem of the homeless mentally ill, including increased government funding for affordable housing, partnerships between the public and private sector to provide job training, and legal reform.

The critical need for well-trained, dedicated professional clinical case managers. “Without excellent clinical case managers, a mental health system will tend to be mechanistic, inaccessible, and exclusively focused on the management of symptoms with medication, rather than also on clients’ human development and rehabilitation,” Dr. Okin asserts.

What everyone can do to overcome the stigma of mental illness and prevent homelessness, with the goal of not just social acceptance for people with mental illness but genuine inclusion in society. “Treatment cannot occur first and inclusion second,” stresses Dr. Okin.

Robert L. Okin, MD, served as chief of psychiatry at San Francisco General Hospital and professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco, for 17 years. He is also a former state commissioner of mental health for both Vermont and Massachusetts. Throughout his career, he developed crucial services and clinical case management programs to enable mentally ill people to live with dignity in the community. A member of the board of advisors of Disabilities Rights International (DRI), he has provided psychiatric advocacy and consultation for missions to Mexico and Turkey, among many other countries, to investigate human rights violations in mental institutions. He lives in San Francisco.

I hope you will be moved, uplifted, and outraged by the stories in SILENT VOICES.

Dr. Robert Okin, Author of SILENT VOICES

- You’ve forged relationships with the homeless, but you’re a trained psychiatrist. What can the average person do to help a homeless person they see on the street?

It is true that I was able to forge such relationships, but I don’t think this primarily resulted from any particular skill I had as a psychiatrist. It was more the result of my openness and expressed interest in the people I met. This may sound corny, but saying a simple “Hello, I hope you have a good day” or “I wish you well” is probably the best and easiest thing to do. It won’t change the actual living conditions of the homeless people, but at least it will make them feel that they’re not invisible. It would be great if you could follow up with an e-mail to your city supervisors and congressperson about the need for supportive housing for homeless people. And if you really want to move this project forward, get your friends to send e-mails as well.

- What is the root of society’s fear and stigmatization of mental illness?

Some of society’s fear comes from the strangeness and unpredictability people associate, sometimes correctly, with mental illness. Because mentally ill people seem strange, it’s hard for us to empathize with them and to remember that they were once children with hopes and dreams like our own. At a deeper level, people have always projected the most feared and hated parts of themselves onto those who have mental illness. Mentally ill people become the living representation of the most disavowed parts of ourselves and thus become stigmatized. Not wanting to be reminded of these parts of ourselves, we, as a society, have burned these people, drowned them, isolated them in mental hospitals, and put them away in jails where we can’t see them. But those who become homeless and aren’t put out of sight evoke in us responses that cause us to avoid them in other ways: basically, we close our eyes to them.

- Did you have any preconceived ideas about the homeless? What was your biggest misconception about them?

I expected to be dismissed and rejected when I reached out to them. I was a stranger, so I assumed they wouldn’t want to talk with me. I also assumed that if they did, they wouldn’t reveal their feelings. I was wrong on all counts. Most of the people I met genuinely welcomed my overtures and quickly warmed up to me. I was repeatedly surprised at how much grief these people were carrying just under the surface and how willing they were to reveal it to me. More than anything else, I was reminded of just how human and vulnerable these people are. I easily identified with and felt close to them. At the end of a day of talking with them, I felt sad, wrung out, and anxious about my grip on my own financial and emotional security.

- How did your own opinions change after meeting and getting to know some of them?

I developed an abiding admiration for many of them—I respected how they were willing to continue living, despite the brutal conditions they were dealing with day after day. I often wondered if I would have the grit and the courage to stick it out if I were in their position. I don’t know if I could stand living their lives and dealing with the hopelessness most of them feel.

- What percentage of the homeless suffer from mental illness?

Approximately 25 percent primarily have severe and chronic mental illness and another 15 percent have significant drug abuse disorders.

- What can city and state governments do to help the homeless mentally ill integrate back into society?

First, these people need supportive, supervised housing and a sufficient income that allows them to escape the deprivations of poverty. Without housing, any other intervention is ineffective. Second, they need case management from a social worker with a relatively small caseload who has the time to meet them where they live, provide a loving human connection with them, help them with their daily tasks (laundry, shopping, budgeting), help them reduce their drug intake, and when indicated, help them to be evaluated by a psychiatrist to get them on psychiatric medications. These social workers also have to play a major advocacy role in helping their clients rejoin society. And third, the homeless mentally ill need something productive to do during the day—some sort of job.