By Rabbi Yonason Goldson

After yesterday’s terrorist bus bombing in Jerusalem, the first in years, Jews around the world felt the painful reminder of our precarious place among nations dedicated to our destruction. With the Passover festival approaching, these thoughts from 2005 remind us that Holocaust is not a phenomenon of the last century, or even the last millennium.

The extermination of six million Jews in the Nazi death camps represents but the most recent in a long history of Jewish holocausts. It was preceded by the Chmielnicki massacres in 17th century Poland, the Almohad massacres in 12th century Spain, the Inquisition and the Crusades and the relentless spilling of blood by the Roman legions – all these and similar chapters in the long, brutal history of attempted genocide against the Jewish people.

When did it all begin?

According to Jewish tradition, it began 3328 years ago, when nearly two and a half million Jews died in a single night.

It was the beginning of the plague of darkness, the penultimate blow in the systematic destruction of the Egyptians and their empire. Pharaoh had already released his Jewish slaves from their oppressive labor midway through the cycle of plagues, driven by the desperate hope that he could appease the G-d of the Jews. But he refused to grant them permission to leave.

For some Jews, the relaxation from their burdens offered an opportunity to reflect upon the responsibilities of freedom and the opportunity that had been promised them to build their own nation. For others, however, it gave time to grow comfortable in the paradise that was Egypt, to adopt an attitude of entitlement for their new-found prosperity, to forget that freedom is never free.

During their 210 years as slaves in Egypt, the Jews had gradually absorbed the corrupt values of that culture, its idolatry and its immorality, retaining only their names, their language, and their style of dress to set themselves apart from their Egyptian hosts. With no merit to deserve divine redemption, the Jewish people received their exodus on credit, credit to be repaid by accepting the Ten Commandments at Sinai and committing themselves to the higher moral and ethical standards of G-d’s chosen people.

600,000 Jews – 20% of their total number – accepted these terms, preparing themselves psychologically and physically to exchange the comfort and familiarity of Egypt for the uncertainty of the empty desert. Four times as many rejected the condition, refusing to make good, as it were, on the credit extended them from heaven, convincing themselves that, with the Egyptians humbled and the yoke of slavery removed from their necks, they could void their contract with the Almighty and remain unencumbered in the land of their former servitude.

The human condition, however, is never static. One who stops growing immediately begins to die; one who stops moving forward instantly begins to slip backward. There is no standing still, no place to rest in this restless world, and the 2,400,000 Jews who thought to deny their destiny, who imagined they could stop the sands of time and were buried by them instead.

The fate of the 80% was not divine vengeance; it was spiritual inevitability. To survive for thirty three centuries, the Jewish nation would have to appreciate that it had no alternative other than survival. Assimilation, conversion, or abdication of Jewish identity may at times have seemed an attractive option to the burden of living as Jews, but the consequences of spiritual extinction are every bit as grave – indeed, much more so – than those of physical extinction.

Ask the Spanish Jews who converted to Christianity, only to be called marranos – pigs – by their Christian brothers and to be burned at the stake in the auto-de-fe of the Inquisition, if their abandonment of Jewish identity was worth the price. Ask the assimilated German Jews stripped of their property, forced to wear yellow stars, and incinerated in Nazi crematoria if they met a better end than those who refused to disavow their Judaism.

Indeed, the narrative of the exodus testifies that, as the Jews prepared to leave the ruins of Egypt after the plague upon the firstborn, “the Almighty gave the people favor in the eyes of the Egyptians.” As slaves forfeiting their identity within Egyptian society, the Egyptians regarded the Jews only with disdain. Once the Jews began to act with Jewish dignity, their former oppressors could not help but respect them.

And so it has been ever since. When we live as Jews, the rest of the world respects us for our values and our conviction. When we shirk our responsibility as upholders of morality to accommodated the ever-changing moral whims of the world around us, we bring upon ourselves nothing but suffering.

The freedom we celebrate at Passover is the freedom to remain true to who we are, who we always have been: The nation that introduced the world to the very concept of freedom, and the nation which has shown the world through the ages that the price of freedom is far less dear than the price of forsaking it.

Image removed by sender.

Rabbi Goldson, aka The Hitchhiking Rabbi, has been teaching and writing in different venues, for decades. He brings a depth of perspective to his commentary on social and political issues, and isn’t your average pundit.

He has spent two decades formulating traditional, conservative, and religious values into a language that doesn’t just preach to the choir but can promote positive debate between the right and the left, as a columnist for the very liberal St. Louis Post-Dispatch and Baltimore Sun and for the very conservative Jewish World Review, among many others.

Image removed by sender.

The Eunoia Agency, Bee Ridge, Sarasota, FL 34233

SafeUnsubscribe™ paul.sladkus@goodnewsbroadcast.com

Forward this email | Update Profile | About our service provider

Sent by deborah.eunoia@gmail.com in collaboration with

Image removed by sender. Constant Contact

Try it free today

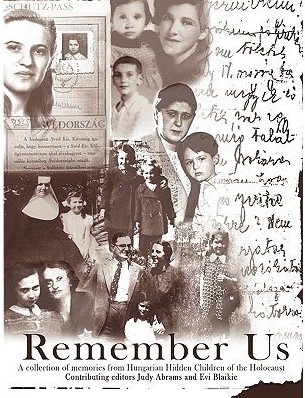

The Film “Remember Us”

The Film “Remember Us”