Peruvian cuisine has gone global, with new restaurants springing up everywhere from Santiago to Soho. On an Amazonian cruise, Andrew Purvis meets the Japanese superchef whose experiments with Asian-Peruvian fusion began in Lima nearly 40 years ago.

Peruvian cuisine has gone global, with new restaurants springing up everywhere from Santiago to Soho. On an Amazonian cruise, Andrew Purvis meets the Japanese superchef whose experiments with Asian-Peruvian fusion began in Lima nearly 40 years ago.

In the observation deck of the M/V Aria, the most opulently-appointed cruise ship on the Amazon, there is less appetite than usual for the communal Jacuzzi. Passengers would normally be immersing themselves in the cool, clear water to soak away the heat and humidity of this spot, close to the equator, where the Marañon and Ucayali rivers meet. Today they have formed a huddle round the tub, but no one has ventured in and, on closer inspection, I can see why.

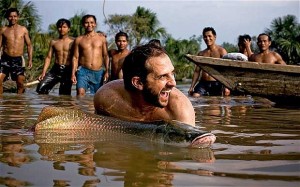

Not only is it filled with muddy river water that smells faintly of methane, but the surface is broken every few minutes by a gargantuan fish. “It’s a paiche,” says Victor Coelho, one of four naturalist guides on board, leaping into the Jacuzzi in his shorts to wrestle with the prehistoric leviathan and to present it for a photo opportunity. “The paiche is at the top of the food chain and has a bony tongue to rake in smaller fish. Like a mammal, it has to surface every five or 10 minutes for oxygen. A large fish could feed a family for a week.”

This one will feed 32 passengers at a dinner showcasing the talents of five top chefs, among them Nobu Matsuhisa – owner of more than 30 restaurants worldwide, including two in London with a Michelin star each – and Yoshihiro Murata, arguably the most influential chef in Japan. His Kikunoi restaurant in Kyoto has three Michelin stars while Roan Kikunoi (also in Kyoto) and Akasaka Kikunoi (in Tokyo) have two stars each. In Peru for a conference, they have been invited to cook on board by Pedro Miguel Schiaffino, the Aria’s executive chef, himself dubbed “South America’s Heston Blumenthal” for his use of esoteric ingredients both here and at Malabar, his acclaimed restaurant in Lima.

On the 147ft-long Aria and its sister ship the Aqua, both operated by Aqua Expeditions, gastronomy is high on the agenda. Last September the Aria hosted Ferran Adrià, of El Bulli fame, with Gastón Acurio – the chef who, seven years ago, took Peruvian cuisine to new heights and has promoted it worldwide in his 33 restaurants. Both were in Lima for Mistura, South America’s biggest food festival, along with René Redzepi of Noma in Copenhagen. Book a cruise on the Aria, and there is a strong chance of a culinary happening in addition to the gourmet meals that come as standard.

In the mornings and afternoons, passengers set out on motorised skiffs with the Aria’s naturalist guides – all local – to fish for piranhas and spot pink river-dolphins, caimans, iguanas, monkeys, bats, sloths and a bewildering variety of birds in the Pacaya Samiria National Reserve west of Iquitos, the main city in the Peruvian rainforest. One day they might release baby turtles back into the wild, the next they might visit a sanctuary for manatees, seal-like river mammals. They arrive back in time for a rain shower in their air-conditioned, Italian-styled suite, followed by a pisco sour (grape brandy, lime juice, sugar, egg white), elegantly mixed by Robinson the bartender, and a sumptuous Peruvian feast.

Over a chilled Cusqueña beer on the night of the five-chef showdown, I ask Nobu about the paiche in the Jacuzzi. Is it already sushi? “We slaughtered it out there, then I tenderised it with vegetables,” he says. “I used broccoli, ginger, celery, tomato, garlic, chilli, kombu [kelp], wakame [sweet seaweed] and two others… 10 vegetables, all finely chopped to produce the enzymes that make the paichesoft. You marinade it for one hour only and the enzymes do their work. There’s no oil, no sugar, just salt and all those vegetable flavours.”

When I cut into the fish later, it does indeed have a soft, fluffy texture and is virtually boneless, unlike chef Murata’s dish of gamitana – a fruit-eating piranha with an earthy taste, like trout – coated in a paste of mocambo, a subtly sweet jungle fruit the colour of butternut squash. Cross-stitched with small bones, this fish is not a great joy to eat, but the combination of flavours rewards the senses. Also on the menu is “dangerous manioc”: grated wild cassava that is strained, boiled for hours to remove toxins, then made into a gelatinous soup with fish, manioc flour and jambu, a mildly anaesthetic Amazonian herb that numbs the tongue but is spicy and pleasantly warming.

Other dishes during my four-day cruise include tagliatelle of chonta (palm heart) in a clear stock flavoured with smoked pork and, floating in it, a nugget of catfish and some freshwater shrimps the size of grains of rice; a free-range hen with black quinoa, similar to mung beans in texture, from the High Andes; a leg of chicken standing upright, with quartered hard-boiled eggs and rice packed around it, wrapped in a jungle leaf; catfish skewers; the chopped, spicy meat of an Amazon snail in its huge shell; and pacamoto, fish cooked inside a bamboo tube, traditionally over coals but, on the Aria, grilled.

It’s a little off-piste for some diners, but you can’t say the food isn’t fresh and local. Regional produce is close to the heart of Schiaffino, though his menu rotates from Amazonian to Japanese to Italian (because the Aria’s owner, Francesco Galli Zugaro, is Italian) to “Chifa”, the curious Chinese-Peruvian fusion seen in garish Asian-styled restaurants all over Peru.

Created and evolved by Chinese immigrants who came here as free labour after the abolition of slavery in 1854, Chifa sprang from the enforced substitution of traditional Chinese ingredients with local ones. A good example is lomo saltado – strips of beef marinaded in vinegar and soy sauce, stir-fried with red onions, Peruvian yellow chillis, wild coriander and tomatoes. In similar fashion, Japanese immigrants invented their own fusion style, “Nikkei”, when they arrived at the turn of the century to work, mainly in agriculture.

In his restaurants, Nobu puts his own sophisticated spin on Nikkei. At Nobu London, the menu includes ceviche (raw fish marinaded in lime juice, garlic, coriander and red chilli, garnished with red onion) and tiradito (a subtler version, with the fish sliced more thinly, like a carpaccio, and no onion). Salmon, beef, chicken and vegetables are given a South American kick with aji panca and aji amarillo, red and yellow hot chilli peppers. Why, I ask Nobu, does he feel such an affinity with Peruvian ingredients, dishes and methods?

“I married my wife in 1972, in Japan,” he explains, “and in 1973 we came to Peru and lived here for a few years. Some Japanese-Peruvian friends invited me to open a traditional Japanese restaurant, Matsuei, with them in Lima.” Unable to find the ingredients he took for granted in Japan, he too had to improvise, hence his trademark style of transcontinental fusion. “My first daughter was born in Lima,” he says, “and we were invited to Iquitos, in the Amazon, by my business partner’s family. My wife couldn’t go with the baby, of course, so I brought my mother to show her the jungle.”

Thirty-eight years later, Nobu is back – a changed man with a Bulgari watch on his wrist and a restaurant empire to his name, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Giorgio Armani and Robert De Niro (who co-owns some Nobu restaurants), a friendship that landed him a part in Martin Scorsese’s Casino. Other roles followed as Mr Roboto in Austin Powers: Goldmember and as a kimono artist in Memoirs of a Geisha. Despite his Hollywood lifestyle, he has not forgotten his time spent in Peru as a young chef and the way the experience influenced his future. “I remembered the ceviches I’d had,” he says, “and I thought, why not do that in my own restaurants?”

More than anything it is the use of raw fish that links the two countries, as Nobu has observed during his frequent visits over the past 15 years. “In Japan we eat a lot of raw fish,” he says, “with soy sauce and wasabi always. Here, the raw fish is marinaded in lime juice. It’s the same product eaten in a completely different way. At one time, Peruvians marinaded their fish for four or five hours. Japanese people know that, after that time, it doesn’t taste much of fish! I’m not saying I did it, but the Japanese had an influence on how Peruvians prepare raw fish. Now, it’s marinaded for just three minutes.”

It’s the healthiest fast food imaginable – an overdose of vitamin C, plus lots of omega 3 – but at an on-board lecture by Victor Coelho about rainforest culture, I learn about deficits in the local diet that are impossible to address. “We eat lots of fish and fruit but very little calcium,” he says. “Bone problems such as osteoporosis are very common, especially among pregnant women.”

At the noisy, chaotic and malodorous food market in Belen, the third-biggest port city in the Amazon after Belém and Manaus (both in Brazil), an Amerindian woman demonstrates how to make the most of the small amount of calcium there is. Preparing fish for the charcoal grill, she makes dozens of incisions in the skin on both sides to cut the smaller, bristle-like bones into manageable shards that won’t get stuck in the throat. Digested, they provide some calcium, but it isn’t nearly enough. These are desperate measures.

Elsewhere in these narrow streets lined with stalls and rammed with hooting motorised rickshaws, I see rows of a boneless shark catfish, mota, the best for making ceviche; palometas (round, saucer-like silver fish), snails, corvina (bass) and freshwater crabs, in which Nobu shows a particular interest. “In Japan we use crab to lower the body temperature and ginger to raise it again,” he says, pointing to the moist tubers of fresh wild ginger, darker in colour than our dried version, on the stalls around us.

Nobu and Murata are fascinated by a woman making “jungle spaghetti”, long strips of palm heart cut by hand from the tree’s fibrous core, and Schiaffino introduces them to mandarina (a dark green citrus fruit with pale orange flesh) and large knobbly limes found only around Iquitos. “They have a good balance between sweet and sour, and a wonderful aroma,” he says.

As we progress into the market, guarded by what seems like the entire ship’s company (there are 24 staff for 32 passengers), as well as the local police, the scene becomes nightmarish. There are turtles turned on their backs, a caiman leg on a grill, the cloven hooves of peccaries (like wild boar), armadillos splayed wide open, the split pelvises of pigs, and chickens with heart, liver, combs and feet packaged and displayed on the outside.

In a moment of madness, I agree to taste “Amazonian shish kebab”: a fat, creamy caterpillar on a skewer, fried or charcoal-grilled. Known as suri, it is the larval stage of the black palm beetle and is traditionally eaten with green banana, perhaps to make it more palatable. To my surprise, it tastes like pork crackling and is delicious.

This is what you might call bas cuisine, the counterpoint to Schiaffino’s exquisite morsels of haute cuisine, but popular food like this is an important part of Peru’s gastronomic renaissance. “You can define it by region,” he says, “the Amazon, the Andes and the coast, all with their own cuisines.” Layered on top are Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, Italian, French and Portuguese influences, making this the most elaborate fusion cuisine in the world. “We have pre-Hispanic cultures, with their cuisines,” Schiaffino explains, “and an extraordinary geographical position and climate. We are blessed in what we have, but only in the past six or seven years have we begun to professonalise our popular cuisines and give them value.”

Peruvians speak of a time before and after Gastón, meaning Gastón Acurio, whose Lima restaurant, Astrid & Gastón, captures the spirit of the movement and has scions in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela, Spain, Mexico and Argentina. “Before Gastón, every high-quality restaurant was French- or Italian-driven,” Pedro says. “There was a popular cuisine, a Peruvian cuisine, but it was never raised to a professional standard. Seven years ago, Gastón began to change that. He conceptualised what we had on a daily basis, in our homes and in our markets, and took it to another level.”

The Peruvian new wave is not to be confused with Novoandina, the modern style of Andean cuisine that began 20 years ago, the brainchild of Bernardo Roca Rey. “He travelled and saw produce that had never been seen in Lima, mainly from the Andes,” Pedro says. “Chefs started putting things like guinea pig into Lima kitchens, they used quinoa to make quinotto [like risotto], different tubers and papas [potatoes – of which Peru is said to have 3,000 varieties], chillis, tomatoes and mountain herbs. It never really took off, and Gastón was the successor.”

Late last year, Acurio opened a New York outpost, La Mar Cebicheria (an alternative spelling of cevicheria), serving Nikkei-influenced ceviches with tuna, red onion, Japanese cucumber, daikon, avocado, nori and sesame in a tamarind “leche de tigre” – the zesty, milky liquid left after making a ceviche. Also on the menu are upmarket anticuchos (meat skewers) enlivened with spicy peppers. Due to open this month is Ceviche in Soho, London, championing freshly caught sustainable fish “cold-cooked” in lime and chilli in the Peruvian style, and a pisco bar, the first in Britain.

Such is the buzz that a New York consultancy group, Baum + Whiteman, is predicting that this year Peruvian cuisine will be adopted by forward-thinking restaurateurs, with a wave of openings in North America and Europe. They will come a pale second to the experience of champagne at sunset on a skiff navigating the blackwater tributaries of the world’s mightiest river, followed by Schiaffino’s edible Amazonian adventures in miniature.