Ash Wednesday is a Christian holy day of prayer, fasting, and repentance.[2] It is preceded by Shrove Tuesday and falls on the first day of Lent,[3] the six weeks of penitence before Easter. Ash Wednesday is observed by many Christians, including Anglicans, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Old Catholics, Methodists, Presbyterians, Roman Catholics,[note 1] and some Baptists.[6]

| Ash Wednesday | |

|---|---|

A cross of ashes/dust on a worshiper’s forehead

|

|

| Observed by | Many Christians |

| Observances | Holy Mass, Service of worship, Divine Service, Divine Liturgy Placing of ashes on the head |

| Date | Wednesday in seventh week before Easter |

| 2018 date | February 14 |

| 2019 date | March 6[1] |

| 2020 date | February 26 |

| 2021 date | February 17 |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Shrove Tuesday/Mardi Gras Carnival Lent Easter |

Ash Wednesday derives its name from the placing of repentance ashes on the foreheads of participants to either the words “Repent, and believe in the Gospel” or the dictum “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”[7] The ashes may be prepared by burning palm leaves from the previous year’s Palm Sunday celebrations.

Because it is the first day of Lent, many Christians, on Ash Wednesday, often begin marking a Lenten calendar, praying a Lenten daily devotional, and abstaining from a luxury that they will not partake of until Easter arrives.[8]

Contents

ObservancesEdit

Fasting and abstinenceEdit

Many Christian denominations emphasize fasting, as well as abstinence during the season of Lent and in particular, on its first day, Ash Wednesday. The First Council of Nicæa spoke of Lent as a period of fasting for forty days, in preparation for Eastertide.[9] In many places, Christians historically abstained from food for a whole day until the evening, and at sunset, Western Christians traditionally broke the Lenten fast, which is often known as the Black Fast.[10][11] In India and Pakistan, many Christians continue this practice of fasting until sunset on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, with some fasting in this manner throughout the whole season of Lent.[12]

In the Roman Catholic Church, Ash Wednesday is observed by fasting, abstinence from meat, and repentance – a day of contemplating one’s transgressions. On Ash Wednesday and Good Friday, Roman Catholics between the ages of 18 and 59 (whose health enables them to do so) are permitted to consume one full meal, along with two smaller meals, which together should not equal the full meal. Some Catholics will go beyond the minimum obligations put forth by the Church and undertake a complete fast or a bread and water fast until sunset. Ash Wednesday and Good Friday are also days of abstinence from meat (mammals and fowl), as are all Fridays during Lent.[13] Some Roman Catholics continue fasting throughout Lent, as was the Church’s traditional requirement,[14]concluding only after the celebration of the Easter Vigil. Where the Ambrosian Rite is observed, the day of fasting and abstinence is postponed to the first Friday in the Ambrosian Lent, nine days later.[15]

A number of Lutheran parishes teach communicants to fast on Ash Wednesday, with some people choosing to continue doing so throughout the entire season of Lent, especially on Good Friday.[16][17][18][19] One Lutheran congregation’s A Handbook for the Discipline of Lent recommends that the faithful “Fast on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday with only one simple meal during the day, usually without meat”.[20]

In the Church of England, and throughout much of the Worldwide Anglican Communion, the entire forty days of Lent are designated days of fasting, while the Fridays are also designated as days of abstinence in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer,[21]with the Traditional Saint Augustine’s Prayer Book: A Book of Devotion for Members of the Anglican Communion defining “Fasting, usually meaning not more than a light breakfast, one full meal, and one half meal, on the forty days of Lent.”[22] The same text defines abstinence as refraining from flesh meat on all Fridays of the Church Year, except for those during Christmastide.[22]

The historic Methodist homilies regarding the Sermon on the Mount stress the importance of the Lenten fast, which begins on Ash Wednesday.[23] The United Methodist Church therefore states that:

There is a strong biblical base for fasting, particularly during the 40 days of Lent leading to the celebration of Easter. Jesus, as part of his spiritual preparation, went into the wilderness and fasted 40 days and 40 nights, according to the Gospels.[24]

Rev. Jacqui King, the minister of Nu Faith Community United Methodist Church in Houston explained the philosophy of fasting during Lent as “I’m not skipping a meal because in place of that meal I’m actually dining with God”.[25]

The Reformed Church in America describes Ash Wednesday as a day “focused on prayer, fasting, and repentance.”[2] The liturgy for Ash Wednesday thus contains the following “Invitation to Observe a Lenten Discipline” read by the presider:[26]

We begin this holy season by acknowledging our need for repentance and our need for the love and forgiveness shown to us in Jesus Christ. I invite you, therefore, in the name of Christ, to observe a Holy Lent, by self-examination and penitence, by prayer and fasting, by practicing works of love, and by reading and reflecting on God’s Holy Word.[26]

Many of the Churches in the Reformed tradition retained the Lenten fast in its entirety, although it was made voluntary, rather than obligatory.[27]

AshesEdit

Ashes are ceremonially placed on the heads of Christians on Ash Wednesday, either by being sprinkled over their heads or, in English-speaking countries, more often by being marked on their foreheads as a visible cross. The words (based on Genesis 3:19) used traditionally to accompany this gesture are, “Memento, homo, quia pulvis es, et in pulverem reverteris.” (“Remember, man, that thou art dust, and to dust thou shalt return.”) This custom is credited to Pope Gregory I the Great (c. 540–604).[29] In the 1969 revision of the Roman Rite, an alternative formula (based on Mark 1:15) was introduced and given first place “Repent, and believe in the Gospel” and the older formula was translated as “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” The old formula, based on the words spoken to Adam and Eveafter their sin,[30] reminds worshippers of their sinfulness and mortality and thus, implicitly, of their need to repent in time.[31] The newer formula makes explicit what was only implicit in the old.

Various manners of placing the ashes on worshippers’ heads are in use within the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, the two most common being to use the ashes to make a cross on the forehead and sprinkling the ashes over the crown of the head. Originally, the ashes were strewn over men’s heads, but, probably because women had their heads covered in church, were placed on the foreheads of women.[32] In the Catholic Church the manner of imposing ashes depends largely on local custom, since no fixed rule has been laid down.[28] Although the account of Ælfric of Eynsham shows that in about the year 1000 the ashes were “strewn” on the head,[33] the marking of the forehead is the method that now prevails in English-speaking countries and is the only one envisaged in the Occasional Offices of the Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea, a publication described as “noticeably Anglo-Catholic in character”.[34] In its ritual of “Blessing of Ashes”, this states that “the ashes are blessed at the beginning of the Eucharist; and after they have been blessed they are placed on the forehead of the clergy and people.”[34] The Ash Wednesday ritual of the Church of England, Mother Church of the Anglican Communion, contains “The Imposition of Ashes” in its Ash Wednesday liturgy.[35] On Ash Wednesday, the Pope, the Bishop of Rome, traditionally takes part in a penitential procession from the Church of Saint Anselm to the Basilica of Santa Sabina, where, in accordance with the custom in Italy and many other countries, ashes are sprinkled on his head, not smudged on his forehead, and he places ashes on the heads of others in the same way.[36]

The Anglican ritual, used in Papua New Guinea states that, after the blessing of the ashes, “the priest marks his own forehead and then the foreheads of the servers and congregation who come and kneel, or stand, where they normally receive the Blessed Sacrament.”[34] The corresponding Catholic ritual in the Roman Missal for celebration within Mass merely states: “Then the Priest places ashes on the head of those present who come to him, and says to each one …”[37] Pre-1970 editions had much more elaborate instructions about the order in which the participants were to receive the ashes, but again without any indication of the form of placing the ashes on the head.[38]

The 1969 revision of the Roman Rite inserted into the Mass the solemn ceremony of blessing ashes and placing them on heads, but also explicitly envisaged a similar solemn ceremony outside of Mass.[37] The Book of Blessings contains a simple rite.[28]While the solemn rite would normally be carried out within a church building, the simple rite could appropriately be used almost anywhere. While only a priest or deacon may bless the ashes, laypeople may do the placing of the ashes on a person’s head. Even in the solemn rite, lay men or women may assist the priest in distributing the ashes. In addition, laypeople take blessed ashes left over after the collective ceremony and place them on the head of the sick or of others who are unable to attend the blessing.[28][39] (In 2014, Anglican Liverpool Cathedral likewise offered to impose ashes within the church without a solemn ceremony.)[40]

In addition, those who attend such Catholic services, whether in a church or elsewhere, traditionally take blessed ashes home with them to place on the heads of other members of the family,[41] and it is recommended to have envelopes available to facilitate this practice.[42] At home the ashes are then placed with little or no ceremony.

Unlike its discipline regarding sacraments, the Catholic Church does not exclude from receiving sacramentals, such as the placing of ashes on the head, those who are not Catholics and perhaps not even baptized.[39] Even those who have been excommunicated and are therefore forbidden to celebrate sacramentals are not forbidden to receive them.[43] After describing the blessing, the rite of Blessing and Distribution of Ashes (within Mass) states: “Then the Priest places ashes on the heads of all those present who come to him.”[37] The Catholic Church does not limit distribution of blessed ashes to within church buildings and has suggested the holding of celebrations in shopping centres, nursing homes, and factories.[42] Such celebrations presume preparation of an appropriate area and include readings from Scripture (at least one) and prayers, and are somewhat shorter if the ashes are already blessed.[44]

The Catholic Church states that the ashes should be those of palm branches blessed at the previous year’s Palm Sundayservice,[37] while a Church of England publication says they “may be made” from the burnt palm crosses of the previous year.[34][35] These sources do not speak of adding anything to the ashes other than, for the Catholic liturgy, a sprinkling with holy water when blessing them. An Anglican website speaks of mixing the ashes with a small amount of holy water or olive oil as a fixative.[45]

Where ashes are placed on the head by smudging the forehead with a sign of the cross, many Christians choose to keep the mark visible throughout the day. The churches have not imposed this as an obligatory rule, and the ashes may even be wiped off immediately after receiving them;[46][47] but some Christian leaders, such as Lutheran pastor Richard P. Bucher and Catholic bishop Kieran Conry, recommend it as a public profession of faith.[48][49] Morgan Guyton, a Methodist pastor and leader in the Red-Letter Christian movement, encourages Christians to wear their ashed cross throughout the day as an exercise of religious freedom.[50]

Ashes to GoEdit

Since 2007, some members of major Christian Churches, including Anglicans, Catholics, Lutherans, and Methodists, have participated in the Ashes to Go program, in which clergy go outside of their churches to public places, such as downtowns, sidewalks and train stations, to distribute ashes to passersby,[51][52][53] even to people waiting in their cars for a stoplight to change.[54] The Anglican priest Emily Mellott of Calvary Church in Lombard took up the idea and turned it into a movement, stated that the practice was also an act of evangelism.[55][56]Anglicans and Catholics in parts of the United Kingdom such as Sunderland, are offering Ashes to Go together: Marc Lyden-Smith, the priest of Saint Mary’s Church, stated that the ecumenical effort is a “tremendous witness in our city, with Catholics and Anglicans working together to start the season of Lent, perhaps reminding those who have fallen away from the Church, or have never been before, that the Christian faith is alive and active in Sunderland.”[51] The Catholic Student Association of Kent State University, based at the University Parish Newman Center, offered ashes to university students who were going through the Student Center of that institution in 2012,[57] and Douglas Clark of St. Matthew’s Roman Catholic Church in Statesboro, among others, have participated in Ashes to Go.[58][59] On Ash Wednesday 2017, Father Paddy Mooney, the priest of St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church in the Irish town of Glenamaddy, set up an Ashes to Go station through which commuters could drive and receive ashes from their car; the parish church also had “drive-through prayers during Lent with people submitting requests into a box left in the church grounds without having to leave their car”.[60] Reverend Trey Hall, pastor of Urban Village United Methodist Church, stated that when his local church offered ashes in Chicago “nearly 300 people received ashes – including two people who were waiting in their car for a stoplight to change.”[54] In 2013, churches not only in the United States, but also at least one church each in the United Kingdom, Canada and South Africa, participated in Ashes to Go.[61]Outside of their church building, Saint Stephen Martyr Lutheran Church in Canton offered Ashes to Go for “believers whose schedules make it difficult to attend a traditional service” in 2016.[62] In the United States itself 34 states and the District of Columbia had at least one church taking part. Most of these churches (parishes) were Episcopal, but there were also several Methodist churches, as well as Presbyterian and Catholic churches.[63]

Commination OfficeEdit

Robin Knowles Wallace states that the traditional Ash Wednesday church service includes Psalm 51 (the Miserere), prayers of confession and the sign of ashes.[64] No single one of the traditional services contains all of these elements. The Anglican church’s traditional Ash Wednesday service, titled A Commination,[65] contains the first two elements, but not the third. On the other hand, the Catholic Church‘s traditional service has the blessing and distribution of ashes but, while prayers of confession and recitation of Psalm 51 (the first psalm at Laudson all penitential days, including Ash Wednesday) are a part of its general traditional Ash Wednesday liturgy,[66] they are not associated specifically with the rite of blessing the ashes. The rite of blessing has acquired an untraditional weak association with that particular psalm only since 1970, when it was inserted into the celebration of Mass, at which a few verses of Psalm 51 are used as a responsorial psalm. Coincidentally, it was only about the same time that in some areas Anglicanism resumed the rite of ashes.

In the mid-16th century, the first Book of Common Prayer removed the ceremony of the ashes from the liturgy of the Church of England and replaced it with what would later be called the Commination Office.[67] In that 1549 edition, the rite was headed: “The First Day of Lent: Commonly Called Ash-Wednesday”.[68] The ashes ceremony was not forbidden, but was not included in the church’s official liturgy.[69] Its place was taken by reading biblical curses of God against sinners, to each of which the people were directed to respond with Amen.[70][71] The text of the “Commination or Denouncing of God’s Anger and Judgments against Sinners” begins: “In the primitive Church there was a godly discipline, that, at the beginning of Lent, such persons as stood convicted of notorious sin were put to open penance, and punished in this world, that their souls might be saved in the day of the Lord; and that others, admonished by their example, might be the more afraid to offend. Instead whereof, until the said discipline may be restored again, (which is much to be wished,) it is thought good that at this time (in the presence of you all) should be read the general sentences of God’s cursing against impenitent sinners”.[72] In line with this, Joseph Hooper Maude wrote that the establishment of The Commination was due to a desire of the reformers “to restore the primitive practice of public penance in church”. He further stated that “the sentences of the greater excommunication” within The Comminationcorresponded to those used in the ancient Church.[73] The Anglican Church’s Ash Wednesday liturgy, he wrote, also traditionally included the Miserere, which, along with “what follows” in the rest of the service (lesser Litany, Lord’s Prayer, three prayers for pardon and final blessing), “was taken from the Sarum services for Ash Wednesday”.[73] From the Sarum Rite practice in England the service took Psalm 51 and some prayers that in the Sarum Missal accompanied the blessing and distribution of ashes.[66][74]In the Sarum Rite, the Miserere psalm was one of the seven penitential psalms that were recited at the beginning of the ceremony.[75] In the 20th century, the Episcopal Church introduced three prayers from the Sarum Rite and omitted the Commination Office from its liturgy.[69]

Low church ceremoniesEdit

In some of the low church traditions, other practices are sometimes added or substituted, as other ways of symbolizing the confession and penitence of the day. For example, in one common variation, small cards are distributed to the congregation on which people are invited to write a sin they wish to confess. These small cards are brought forth to the altar table where they are burned.[76]

Regional customsEdit

In Victorian era, theatres refrained from presenting costumed shows on Ash Wednesday, so they provided other entertainment, as mandated by the Church of England (Anglican Church).[77]

In Iceland, children “pin small bags of ashes on the back of some unsuspecting person”,[78] dress up in costumes, and sing songs for candy.[79]

Biblical significance of ashesEdit

Ashes were used in ancient times to express grief. When Tamar was raped by her half-brother, “she sprinkled ashes on her head, tore her robe, and with her face buried in her hands went away crying” (2 Samuel 13:19). The gesture was also used to express sorrow for sins and faults. In Job 42:3–6, Job says to God: “I have heard of thee by the hearing of the ear: but now mine eye seeth thee. Wherefore I abhor myself, and repent in dust and ashes.” The prophet Jeremiah calls for repentance by saying: “O daughter of my people, gird on sackcloth, roll in the ashes” (Jer 6:26). The prophet Daniel recounted pleading to God: “I turned to the Lord God, pleading in earnest prayer, with fasting, sackcloth and ashes” (Daniel 9:3). Just prior to the New Testament period, the rebels fighting for Jewish independence, the Maccabees, prepared for battle using ashes: “That day they fasted and wore sackcloth; they sprinkled ashes on their heads and tore their clothes” (1 Maccabees 3:47; see also 4:39).

Examples of the practice among Jews are found in several other books of the Bible, including Numbers 19:9, 19:17, Jonah3:6, Book of Esther 4:1, and Hebrews 9:13. Jesus is quoted as speaking of the practice in Matthew 11:21 and Luke10:13: “If the mighty works done in you had been done in Tyre and Sidon, they would have repented long ago (sitting) in sackcloth and ashes.”

Christian use of ashesEdit

Christians continued the practice of using ashes as an external sign of repentance. Tertullian(c. 160 – c. 225) said that confession of sin should be accompanied by lying in sackcloth and ashes.[80] The historian Eusebius (c. 260/265 – 339/340) recounts how a repentant apostate covered himself with ashes when begging Pope Zephyrinus to readmit him to communion.[81]

John W. Fenton writes that “by the end of the 10th century, it was customary in Western Europe (but not yet in Rome) for all the faithful to receive ashes on the first day of the Lenten fast. In 1091, this custom was then ordered by Pope Urban II at the council of Benevento to be extended to the church in Rome. Not long after that, the name of the day was referred to in the liturgical books as “Feria Quarta Cinerum” (i.e., Ash Wednesday).”[82]

The public penance that grave sinners underwent before being admitted to Holy Communion just before Easter lasted throughout Lent, on the first day of which they were sprinkled with ashes and dressed in sackcloth. When, towards the end of the first millennium, the discipline of public penance was dropped, the beginning of Lent, seen as a general penitential season, was marked by sprinkling ashes on the heads of all.[83] This practice is found in the Gregorian Sacramentary of the late 8th century.[31][84] About two centuries later, Ælfric of Eynsham, an Anglo-Saxon abbot, wrote of the rite of strewing ashes on heads at the start of Lent.[33][85]

The article on Ash Wednesday in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica states that, after the Protestant Reformation, the ashes ceremony was not forbidden in the Church of England, a statement that may explain the research by Blair Meeks that the Anglican tradition “never lapsed in this observance”.[86] It was even prescribed under King Henry VIII in 1538 and under King Edward VI in 1550, but it fell out of use in many areas after 1600.[69] In 1536, the Ten Articles issued by authority of Henry VIII commended “the observance of various rites and ceremonies as good and laudable, such as clerical vestments, sprinkling of holy water, bearing of candles on Candlemas-day, giving of ashes on Ash-Wednesday”.[87] After Henry’s death in January 1547, Thomas Cranmer, within the same year, “procured an order from the Council to forbid the carrying of candles on Candlemas-day, and the use of ashes on Ash-Wednesday, and of palms on Palm-Sunday, as superstitious ceremonies”, an order that was issued only for the ecclesiastical province of Canterbury, of which Cranmer was archbishop.[88][89][90] The Church Cyclopædia states that the “English office had adapted the very old Salisbury service for Ash-Wednesday, prefacing it with an address and a recital of the curses of Mount Ebal, and then with an exhortation uses the older service very nearly as it stood.”[73][91] The new Commination Office had no blessing of ashes and therefore, in England as a whole, “soon after the Reformation, the use of ashes was discontinued as a ‘vain show’ and Ash Wednesday then became only a day of marked solemnity, with a memorial of its original character in a reading of the curses denounced against impenitent sinners”.[92] The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, in the 19th century, observed Ash Wednesday: “as a day of fasting and humiliation, wherein we are publicly to confess our sins, meekly to implore God’s mercy and forgiveness, and humbly to intercede for the continuance of his favour”.[93] In the 20th century, the Book of Common Prayer provided prayers for the imposition of ashes.[94]

Monte Canfield and Blair Meeks state that after the Protestant Reformation, Anglicans and Lutherans kept the rite of blessing and distributing ashes to the faithful on Ash Wednesday, and that the Protestant denominations that did not keep it encouraged its use “during and after the ecumenical era that resulted in the Vatican II proclamations”.[86][95]Jack Kingsbury and Russell F. Anderson likewise state that the practice was continued among some Anglicans and Lutherans.[96][97] On the other hand, Edward Traill Horn wrote: “The ceremony of the distribution of the ashes was not retained by the reformers, whether Lutheran, Anglican or Reformed”, although these denominations honored Ash Wednesday as the first day of Lent.[98] Frank Senn, a liturgical scholar, has been quoted as saying: “How and why the use of ashes fell out of Lutheran use is difficult to discern from the sources… [C]hurch orders don’t specifically say not to use ashes; they simply stopped giving direction for blessing and distributing them and eventually the pastors just stopped doing it.”[99]

As part of the liturgical revival ushered in by the ecumenical movement, the practice was encouraged in Protestant churches,[95] including the Methodist Church.[100][101] It has also been adopted by Anabaptist and Reformed churches and some less liturgical denominations.[102]

The Eastern Orthodox churches generally do not observe Ash Wednesday,[103] although in recent times, the creation of the Antiochian Western Rite Vicariate has led to the observance of Ash Wednesday among Western Orthodox parishes.[82] In this tradition, ashes “may be distributed outside of the mass or any liturgical service” although “commonly the faithful receive their ashes immediately before the Ash Wednesday mass”.[82] In Orthodoxy, historically, “serious public sinners in the East also donned sackcloth, including those who made the Great Fast a major theme of their entire lives such as hermits and desert-dwellers.”[104] Byzantine Catholics, although in the United States use “the same Gregorian calendar as the Roman Catholic rite”, do not practice the distribution of ashes as it is “not part of their ancient tradition”.[105]

In the Ambrosian Rite, ashes are blessed and placed on the heads of the faithful not on the day that elsewhere is called Ash Wednesday, but at the end of Mass on the following Sunday, which in that rite inaugurates Lent, with the fast traditionally beginning on Monday, the first weekday of the Ambrosian Lent.[106][15][107][108]

LentEdit

Ash Wednesday marks the start of a 40-day period which is an allusion to the separation of Jesus in the desert to fast and pray. During this time he was tempted. Matthew 4:1–11, Mark 1:12–13, and Luke 4:1–13.[109] While not specifically instituted in the Bible text, the 40-day period of repentance is also analogous to the 40 days during which Moses repented and fasted in response to the making of the Golden calf.(Exo. 34:27–28) (Jews today follow a 40-day period of repenting in preparation for and during the High Holy Days from Rosh Chodesh Elul to Yom Kippur.)

DatesEdit

Ash Wednesday is exactly 46 days before Easter Sunday, a moveable feast based on the cycles of the moon. The earliest date Ash Wednesday can occur is 4 February (which is only possible during a common year with Easter on 22 March), which happened in 1598, 1693, 1761 and 1818 and will next occur in 2285.[110] The latest date Ash Wednesday can occur is 10 March (when Easter Day falls on 25 April) which occurred in 1666, 1734, 1886 and 1943 and will next occur in 2038. Ash Wednesday has never occurred on Leap Year Day (29 February), and it will not occur as such until 2096. The only other years of the third millennium that will have Ash Wednesday on 29 February are 2468, 2688, 2840 and 2992. (Ash Wednesday falls on 29 February only if Easter is on 15 April in a leap year starting on a Sunday.)

Observing churchesEdit

These Christian Churches are among those that mark Ash Wednesday with a particular liturgy or service.

- African Methodist Episcopal Church[111]

- African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church[111]

- Anglican Church in North America[112]

- Anglican Communion[113]

- Anglican Continuum[118]

- Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)[119]

- Christian Methodist Episcopal Church[120]

- Some congregations of the Church of the Nazarene[121]

- Community of Christ[122]

- Ecclesia Gnostica[123]

- Evangelical Covenant Church[124]

- Independent Catholic denominations

- Lutheran Churches[126]

- Some Mennonite congregations[128][129]

- Methodist Church in Great Britain[130]

- Metropolitan Community Churches[131]

- Moravian Church[132][133]

- Reformed churches (Presbyterian[134], United Church of Christ, etc.)

- Roman Catholic Church[135]

- United Church of Christ Congregations[136]

- United Methodist Church[120]

- Wesleyan Church[137]

The Eastern Orthodox Church does not, in general, observe Ash Wednesday; instead, Orthodox Great Lent begins on Clean Monday. There are, however, a relatively small number of Orthodox Christians who follow the Western Rite; these do observe Ash Wednesday, although often on a different day from the previously mentioned denominations, as its date is determined from the Orthodox calculation of Pascha, which may be as much as a month later than the Western observance of Easter.

GalleryEdit

-

The chancel of Palmer Memorial Episcopal Church on Ash Wednesday 2015 (the veiled altar crossand purple paraments are customary during Lent)

-

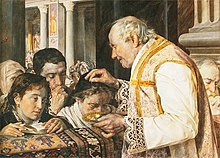

A Methodist minister distributing ashes to confirmands kneeling at the chancel rails on Ash Wednesday in 2016

-

A Lutheran clergyman distributes ashes during the Holy Massat Nazareth Evangelical Lutheran Church in Cedar Falls, Iowa on Ash Wednesday in 2017

National No Smoking DayEdit

In the Republic of Ireland, Ash Wednesday is National No Smoking Day.[138][139] The date was chosen because quitting smoking ties in with giving up luxury for Lent.[140][141] In the United Kingdom, No Smoking Day was held for the first time on Ash Wednesday in 1984[142] but is now fixed as the second Wednesday in March.[143]

NotesEdit

- ^ Not all Catholics observe Ash Wednesday. Eastern Catholic Churches, who do not count Holy Week as part of Lent, begin the penitential season on Clean Monday, the Monday before Ash Wednesday, and Catholics who follow the Ambrosian Ritebegin it on the First Sunday in Lent. Ashes are blessed and ceremonially distributed at the start of Lent throughout the Latin Church and in the Maronite Catholic Church and the Syro-Malabar Catholic Church. In the Ambrosian Rite, this is done at the end of the Sunday Mass or on the following day.[4][5]

ReferencesEdit

- ^ Selected Christian Observances, 2019, U.S. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications Department

- ^ a b “The Liturgical Calendar”. Reformed Church in America. 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Walker, Katie (7 March 2011). “Shrove Tuesday inspires unique church traditions”. Daily American Reporter. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Il Sussidiario, Giorno delle Ceneri: Cos’è il rito delle Ceneri Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sapere, Perché il Carnevale ambrosiano si festeggia in ritardo rispetto al resto d’Italia? Archived 24 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Koonse, Emma (5 March 2014). “Ash Wednesday Today, Christians Observe First Day of Lent”. The Christian Post. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

Although some denominations do not practice the application of ashes to the forehead as a mark of public commitment on Ash Wednesday, those that do include Catholics, Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists, Presbyterians, and some Baptist followers.

- ^ “The Roman Missal [Third Typical Edition, Chapel Edition]”. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016.

- ^ International Journal of Religious Education, Volume 27. National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A. 1950. p. 33.

- ^ Gassmann, Günther; Oldenburg, Mark W. (10 October 2011). Historical Dictionary of Lutheranism. Scarecrow Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780810874824.

The Council of Nicea (325) mentions for the first time Lent as a period of 40 days of fasting in preparation for Easter.

- ^ Cléir, Síle de (5 October 2017). Popular Catholicism in 20th-Century Ireland: Locality, Identity and Culture. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 101. ISBN 9781350020603.

Catherine Bell outlines the details of fasting and abstinence in a historical context, stating that the Advent fast was usually less severe than that carried out in Lent, which originally involved just one meal a day, not to be eaten until after sunset.

- ^ Guéranger, Prosper; Fromage, Lucien (1912). The Liturgical Year: Lent. Burns, Oates & Washbourne. p. 8.

St. Benedict’s rule prescribed a great many fasts, over and above the ecclesiastical fast of Lent; but it made this great distinction between the two: that whilst Lent obliged the monks, as well as the rest of the faithful, to abstain from food till sunset, these monastic fasts allowed the repast to be taken at the hour of None.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ “Some Christians observe Lenten fast the Islamic way”. Union of Catholic Asian News. 27 February 2002. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ 1983 Code of Canon Law, canon 1251

- ^ 1917 Code of Canon Law, canon 1252 §§2–3

- ^ a b “Il Tempo di Quaresima nel rito Ambrosiano” [The time of Lent in the Ambrosian rite] (PDF) (in Italian). Parrocchia S. Giovanna Antida Thouret. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

Il rito di Imposizione delle ceneri andrebbe celebrato il Lunedì della prima settimana di Quaresima, ma da sempre viene celebrato al termine delle Messe della prima domenica di Quaresima. … I venerdì di Quaresima sono di magro, ed il venerdì che segue la I Domenica di Quaresima è anche di digiuno.

- ^ Hatch, Jane M. (1978). The American Book of Days. Wilson. p. 163. ISBN 9780824205935.

Special religious services are held on Ash Wednesday by the Church of England, and in the United States by Episcopal, Lutheran, and some other Protestant churches. The Episcopal Church prescribes no rules concerning fasting on Ash Wednesday, which is carried out according to members’ personal wishes; however, it recommends a measure of fasting and abstinence as a suitable means of marking the day with proper devotion. Among Lutherans as well, there are no set rules for fasting, although some local congregations may advocate this form of penitence in varying degrees.

- ^ Gassmann, Günther; Oldenburg, Mark W. (10 October 2011). Historical Dictionary of Lutheranism. Scarecrow Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780810874824.

In many Lutheran churches, the Sundays during the Lenten season are called by the first word of their respective Latin Introitus (with the exception of Palm/Passion Sunday): Invocavit, Reminiscere, Oculi, Laetare, and Judica. Many Lutheran church orders of the 16th century retained the observation of the Lenten fast, and Lutherans have observed this season with a serene, earnest attitude. Special days of eucharistic communion were set aside on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday.

- ^ Pfatteicher, Philip H. (1990). Commentary on the Lutheran Book of Worship: Lutheran Liturgy in Its Ecumenical Context. Augsburg Fortress Publishers. pp. 223–244, 260. ISBN 9780800603922.

The Good Friday fast became the principal fast in the calendar, and even after the Reformation in Germany many Lutherans who observed no other fast scrupulously kept Good Friday with strict fasting.

- ^ Jacobs, Henry Eyster; Haas, John Augustus William (1899). The Lutheran Cyclopedia. Scribner. p. 110.

By many Lutherans Good Friday is observed as a strict fast. The lessons on Ash Wednesday emphasize the proper idea of the fast. The Sundays in Lent receive their names from the first words of their Introits in the Latin service, Invocavit, Reminiscere, Oculi, Lcetare, Judica.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Weitzel, Thomas L. (1978). “A Handbook for the Discipline of Lent” (PDF). Rev. Thomas L. Weitzel. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Buchanan, Colin (22 October 2015). Historical Dictionary of Anglicanism. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 256. ISBN 9781442250161.

- ^ a b Gavitt, Loren Nichols (1991). Traditional Saint Augustine’s Prayer Book: A Book of Devotion for Members of the Anglican Communion. Holy Cross Publications.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Abraham, William J.; Kirby, James E. (24 September 2009). The Oxford Handbook of Methodist Studies. Oxford University Press. pp. 257–. ISBN 978-0-19-160743-1.

- ^ “What does The United Methodist Church say about fasting?”. The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 1 March2017.

- ^ Chavez, Kathrin (2010). “Lent: A Time to Fast and Pray”. The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 1 March2017.

- ^ a b “Ash Wednesday”. Reformed Church in America. 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (1911). The Encyclopaedia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopaedia Britannica. p. 428.

The Lenten fast was retained at the Reformation in some of the reformed Churches, and is still observed in the Anglican and Lutheran communions.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e ZENIT Staff. “Laypeople Distributing Ashes”. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ Olsen, Ted (August 2008). “The Beginning of Lent”. Christianity Today. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ The biblical text does not have the words “remember that”, nor the vocative noun “homo” (human being) that is included in the pre-1970 Latin version of the formula.

- ^ a b Richard P. Bucher, “The History and Meaning of Ash Wednesday” Archived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ McNamara, Edward. “Ashes and How to Impose Them”. ZENIT News Agency. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ a b The Lives of the Saints: “We read in the books both in the Old Law and in the New that the men who repented of their sins bestrewed themselves with ashes and clothed their bodies with sackcloth. Now let us do this little at the beginning of our Lent that we strew ashes upon our heads to signify that we ought to repent of our sins during the Lenten fast.”

- ^ a b c d “Ash Wednesday Blessing of Ashes”. Occasional Office. Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea. Archived from the original on 27 December 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b Church of England, Lent Material Archived 29 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, p. 230

- ^ “Ash Wednesday: Pope Francis Celebrates at Santa Sabina”. Order of preachers. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d Roman Missal, Ash Wednesday

- ^ Tridentine Roman Missal, “Feria IV Cinerum”

- ^ a b “Responses to frequently asked questions regarding Lenten practices”. Catholics United for the Faith. Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ “Cathedral offers visitors ‘Ashes to Go’ this Ash Wednesday”. Liverpool Cathedral (Anglican). 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Bernd Biege. “Ash Wednesday in Ireland: End of the Good Times, Start of Lent”. About.com Travel. Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ a b Website of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Kildare and Leighlin. Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Code of Canon Law, canon 1331 §1 2° Archived 29 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Order for the Blessing and Distribution of AshesArchived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Lent and Easter”. The Diocese of London. 17 March 2004. Archived from the original on 24 September 2006.

Ash Wednesday marks the first day of Lent, the period of forty days before Easter. It is so called because of the Church’s tradition of making the sign of the cross on people’s foreheads, as a sign of penitence and of Christian witness. The ash is made by burning palm crosses from the previous year and is usually mixed with a little holy water or oil.

- ^ Scott P. Richert. “Should Catholics Keep Their Ashes on All Ash Wednesday?”. About.com Religion & Spirituality. Archived from the original on 12 April 2014.

- ^ Akin, Jimmy. “9 things to know and share about Ash Wednesday”. National Catholic Register. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

There is no rule about this. It is a matter of personal decision based on the individual’s own inclinations and circumstances.

- ^ Bucher, Richard P. “The History and Meaning of Ash Wednesday”. Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

Many Christians choose to leave the ashes on their forehead for the remainder of the day, not to be showy and boastful (see Matthew 6:16–18). Rather, they do it as a witness that all people are sinners in need of repentance AND that through Jesus all sins are forgiven through faith.

- ^ Arco, Anna (3 March 2011). “Don’t rub off your ashes, urges bishop”. The Catholic Herald. Catholic Herald. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

Catholics should try not to rub their ashes off after Ash Wednesday Mass, an English bishop has said. Bishop Kieran Conry of Arundel and Brighton, who heads the department of evangelization and catechesis, urged Catholics across Britain to wear “the outward sign of our inward sorrow for our sins and for our commitment to Jesus as Our Lord and Savior”. He said: “The wearing of the ashes provides us with a wonderful opportunity to share with people how important our faith is to us and to point them to the cross of Christ. I invite you where possible to attend a morning or lunchtime Mass.

- ^ Guyton, Morgan (21 February 2012). “Like Religious Freedom? Wear Ashes on Wednesday!”. Red Letter Christians. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

I strongly believe that wearing ashes on our foreheads on Ash Wednesday is the best way to 1) assert our religious freedom as citizens and 2) remember that our call as Christians is to be witnesses first and foremost.

- ^ a b “Catholics and Anglicans to distribute ashes to shoppers in Sunderland city centre”. The Catholic Herald. 4 February 2016. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

On Wednesday St Mary’s Catholic church and Sunderland Minster, an Anglican church, will be working together to offer “Ashes to Go” – a new approach to a centuries-old Christian tradition.

- ^ Grossman, Cathy Lynn. “Episcopal priests offer ‘Ashes to Go’ as Ash Wednesday begins Lent”. USA Today. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

Dubbed Ashes to Go, it’s a contemporary spin on the Ash Wednesday practice followed chiefly in Episcopal, Anglican, Catholic and Lutheran denominations.

- ^ Banks, Adelle M. (5 March 2014). “‘Ashes to Go’ meets commuters in Washington, D.C.” Religion News Service. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April2014.

Bishop Mariann Edgar Budde, leader of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington, and members of St. Paul’s Parish in Washington, D.C., imposed ashes on commuters and other passers-by on Ash Wednesday (5 March) near the Foggy Bottom Metro station in the nation’s capital.

- ^ a b “Got ashes? Chicago church takes Lent to the streets”. The United Methodist Church. 27 April 2011. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ “About Ashes to Go”. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ Grossman, Cathy Lynn. “Episcopal priests offer ‘Ashes to Go’ as Ash Wednesday begins Lent”. USA Today. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

Anyone can accept the ashes although, Mellott says, non-Christians tend not to seek them. Still, she says, “if anyone does, we view it as an act of evangelism, and we make it clear this is a part of the Christian tradition.”

- ^ Anthony Ezzo (23 February 2012). “Students make time to get ashes”. TV2. Kent Wired. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ Brandon, Loretta. “A modern way to begin the Lenten season”. Statesboro Herald. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

Ministers participating in Ashes to Go include the Rev. Dan Lewis from First Presbyterian Church, the Rev. Joan Kilian from Trinity Episcopal Church, the Rev. Bill Bagwell and the Rev. Jonathan Smith from Pittman Park United Methodist Church, the Rev. Douglas Clark of St. Matthew’s Roman Catholic Church, and the Rev. James Byrd, from St. Andrew’s Chapel Church.

- ^ “Catholics Who Can’t Make it to Church can Get ‘Ashes to Go‘“. KFBK News and Radio. 5 March 2014. Archivedfrom the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

Some Catholics who couldn’t make it to church this morning got their “Ashes on the Go.” Father Tony Prandini with Good Shepherd Catholic Parish was conducting Ash Wednesday rituals – marking foreheads – outside of the State Capitol.

- ^ Farley, Harry (1 March 2017). “#AshesToGo at Start of Lent As Clergy Offer Commuters ‘Ash n’ Dash‘“. Christian Today. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

Commuters can drive in the gate of St Patrick’s Church, in Glenmady, receive ashes from their car and drive out the other side. ‘We looked at the situation on the ground. People and families are on the move all the time,’ parish priest Father Paddy Mooney told the Irish Catholic. ‘It’s about meeting people where they are.’ The same church will also offer drive-through prayers during Lent with people submitting requests into a box left in the church grounds without having to leave their car.

- ^ “What Is ‘Ashes To Go’? Where To Get ‘ATG’ In New York”. International Business Times. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April2014.

In 2012, that initiative, “Ashes to Go,” caught on nationally, and a year later the idea went international, with churches in the United Kingdom, Canada and South Africa also practicing the easy penitence method.

- ^ Coffey, Tim (10 February 2016). “Jackson Township church offers ‘Ashes to Go‘“. WKYC. Retrieved 1 March2017.

- ^ “Where to find Ashes to Go This Year”. Ashes to Go. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ Wallace, Robin Knowles (1 October 2010). The Christian Year: A Guide for Worship and Preaching. Abingdon Press. p. 49. ISBN 9781426731303. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

The service for Ash Wednesday has traditionally included Psalm 51, prayers of confession and the sign of ashes, often in the shape of a cross.

- ^ Mant, Richard (1825). The Book of Common Prayer: And Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the United Church of England and Ireland: Together with the Psalter Or Psalms of David, Pointed as They are to be Sung Or Said in Churches; and the Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons; and the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion: with Notes Explanatory, Practical and Historical, from Approved Writers of the Church of England. W. Baxter. p. 510.

- ^ a b Sylvia A. Sweeney, An Ecofeminist Perspective on Ash Wednesday and Lent Archived 20 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Peter Lang 2010 ISBN 978-1-43310739-9), pp. 107–110

- ^ “The Oxford Guide to The Book of Common Prayer: A Worldwide Survey”. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016.

- ^ Mant, Richard (1825). The Book of Common Prayer: And Administration of the Sacraments, and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church, According to the Use of the United Church of England and Ireland: Together with the Psalter Or Psalms of David, Pointed as They are to be Sung Or Said in Churches; and the Form and Manner of Making, Ordaining, and Consecrating of Bishops, Priests, and Deacons; and the Thirty-nine Articles of Religion: with Notes Explanatory, Practical and Historical, from Approved Writers of the Church of England. Oxford: W. Baxter. p. 506.

- ^ a b c

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 734.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 734. - ^ John Brand, Sir Henry Ellis, James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, Observations on the Popular Antiquities of Great Britain (Bell & Daldy, 1873), vol. 1, p. 98 Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Commination” Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine in Elizabeth A. Livingstone (editor), The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2013 ISBN 978-0-19965962-3)

- ^ Full text at the website of the Church of EnglandArchived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Maude, Joseph Hooper (1901). The History of the Book of Common Prayer. E.S. Gorham. p. 110. Archivedfrom the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

The Commination. This service was composed in 1549. In the ancient services there was nothing that corresponded at all nearly to the first part of this service, except the sentences of the greater excommunication, which were commonly read in parish churches three or four times a year. Some of the reformers were very anxious to restore the primitive practice of public penance in church, which was indeed occasionally practiced, at least until the latter part of the eighteenth century, and they put forward this service as a sort of substitute. The Miserere and most of what follows was taken from the Sarum services for Ash Wednesday.

- ^ Bernard Reynolds, Handbook to the Book of Common Prayer Archived 20 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine(Рипол Классик ISBN 978-58-7386158-3), p. 431

- ^ “The Sarum Missal in English”. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017.

- ^ “Why ashes on Ash Wednesday?”. The United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017.

- ^ Foulkes, Richard. Church and Stage in Victorian Britain. Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 34.

- ^ Lacy, Terry G. (2000). Ring of Seasons: Iceland – Its Culture and History. University of Michigan Press. p. 109. ISBN 9780472086610.

- ^ Einarsdottir, Kristin (2004). „Megum við syngja?“ Rannsókn á öskudagssiðum Íslendinga fyrr og nú. (“Can we sing?” Research on öskudag customs in Iceland, past and present.) (Masters thesis) (in Icelandic). University of Iceland, department of ethnology.

- ^ Tertullian, On Repentance, chapter 9 Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “CHURCH FATHERS: Church History, Book V (Eusebius)”. Archived from the original on 28 February 2011.

- ^ a b c Fenton, John W (2013). “Orthodox Ash Wednesday”. Antiochian Western Rite Vicariate. Archivedfrom the original on 16 April 2014.

- ^ “Ash Wednesday”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

- ^ “Fr. Saunders”. Archived from the original on 7 March 2014.

- ^ The Lives of the Saints: https://archive.org/details/aelfricslivesof01aelf.

- ^ a b Meeks, Blair Gilmer (2003). Season of Ash and Fire: Prayers and Liturgies for Lent and Easter. Abingdon Press. p. 107. ISBN 9780687044542. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

In recent years Christians from the Reformed branch of the Protestant tradition have begun to recover a practice that dates in the Western church at least to the tenth century. That is to begin Lent on the Wednesday before the First Sunday in Lent with a service of repentance and commitment, including the imposition of ashes. The Lutheran and Anglican traditions, of course, never lapsed in this observance, and the liturgical reforms of Vatican II have made Roman Catholic prayers and rubrics more accessible to other traditions through ecumenical dialogues.

- ^ Schaff, Philip (1877). A History of the Creeds of Christendom. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 612.

- ^ Joseph Towers, British Biography (Goadby 1766), vol. 2, p. 275 Archived 4 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Strype, Memorials of Thomas Cranmer (London, Chiswell 1694), p. 159 Archived 6 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Foxe, John Milner, Ingram Cobbin, Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (Knight and Son 1856), p. 500 Archived 1 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Benton, Angelo Ames (1883). The Church Cyclopaedia: A Dictionary of Church Doctrine, History, Organization, and Ritual, and Containing Original Articles on Special Topics, Written Expressly for this Work by Bishops, Presbyters, and Laymen ; Designed Especially for the Use of the Laity of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. L. R. Hamersly. p. 163. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ Robert Chambers, The Book of Days (1862), p. 240Archived 22 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Andrew Fowler, Episcopal Church, An Exposition of the Book of Common Prayer, and Administration of the Sacraments(1805), p. 119 Archived 6 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church: Together with the Psalter Or Psalms of David According to the Use of the Episcopal Church. Church Publishing, Inc. 1979. p. 265. ISBN 9780898690613. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- ^ a b Monte Canfield (20 February 2009). “Ash Wednesday: What is it About?”. Salon. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

After the Reformation most Protestant church denominations, while recognizing Ash Wednesday as a holy day, did not engage in the imposition of ashes. Many Anglican, Episcopal and some Lutheran churches did continue the rite but it was mostly reserved for use in the Roman Catholic Church. During and after the ecumenical era that resulted in the Vatican II proclamations, many of the Protestant denominations encouraged a liturgical revival in their churches and the Ash Wednesday imposition of ashes was encouraged.

- ^ Kingsbury, Jack D.; Pennington, Chester (11 December 1980). Lent. Fortress Press. ISBN 9780800640934. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 16 April2014.

The imposition of ashes symbolizes the penitential nature of the season of Lent. While this custom is still observed in the Roman Catholic church, and in some Lutheran and Anglican parishes, it has not been retained in Reformed churches.

- ^ Anderson, Russell F. (1996). Lectionary Preaching Workbook. CSS Publishing. p. 104. ISBN 9780788008214. Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

Ashes are a traditional symbol of penitence and remorse. The practice of imposing ashes on the first day of Lent continues to this day in the church of Rome as well as in many Lutheran and Episcopalian quarters.

- ^ Edward Traill Horn, The Christian Year (Muhlenberg Press 1957), p. 106 Archived 17 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Ashes on Ash Wednesday”. Gloria Christi Lutheran Church. 12 December 2006. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ William P. Lazarus, Mark Sullivan (31 January 2011). Comparative Religion For Dummies. For Dummies. p. 98. ISBN 9781118052273. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

This is the day Lent begins. Christians go to church to pray and have a cross drawn in ashes on their foreheads. The ashes draw on an ancient tradition and represent repentance before God. The holiday is part of Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Methodist, and Episcopalian liturgies, among others.

- ^ The United Methodist Church website: “When did United Methodists start the “imposition of ashes” on Ash Wednesday?” retrieved 1 March 2014 | “While many think of actions such as the imposition of ashes, signing with the cross, footwashing, and the use of incense as something that only Roman Catholics or high church Episcopalians do, there has been a move among Protestant churches, including United Methodists to recover these more multisensory ways of worship.”

- ^ Baptists mark Ash Wednesday Jeff BrumleyArchived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine 13 February 2013 | While long associated with Catholic and various liturgical Protestant denominations, its observance has spread in recent years to traditions known more for avoiding liturgical seasons than embracing them.

- ^ Ash Wednesday. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2014. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

- ^ Roman, Alexander. “on Fasting”. Ukrainian Orthodoxy. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ Baldwin, Lou (12 March 2009). “Lenten practices differ for Byzantine Catholics”. The Catholic Standard and Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ “Il Rito Ambrosiano” (in Italian). Parrocchie.it. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 June2014.

la Quaresima inizia la domenica successiva al “mercoledì delle ceneri” con l’imposizione delle ceneri al termine della Messa festiva. … Una delle pecularità di questo rito, con profili non-soltanto strettamente religiosi, è l’inizio della Quaresima, che non-parte dal Mercoledì delle Ceneri, ma dalla domenica immediatamente successiva.

- ^ “Ambrosian Liturgy and Rite”. The Catholic Encyclopedia. 2012. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ^ Dipippo, Gregory (16 February 2014). “Septuagesima in the Ambrosian Rite”. New Liturgical Movement. Archivedfrom the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

The Ambrosian Rite still to this day has no Ash Wednesday; it is therefore Quinquagesima that forms the prelude to Lent, properly so-called, which the Roman Rite has in Ash Wednesday and the ferias “post Cineres”.

- ^ “Lent with Jesus in the desert to fight the spirit of evil”. Asia News.it. 3 May 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009.

Turning to the gospel of the day, which is about Jesus’ 40 days in the desert, “where he overcame the temptations of Satan” (cfr Mk 1:12–13), Pope Benedict XVIexhorted Christians to follow “their Teacher and Lord to face together with Him ‘the struggle against the spirit of evil’.” He said: “The desert is rather an eloquent metaphor of the human condition.”

- ^ “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ a b “Cultural Resources: Ash Wednesday”. The African American Lectionary. Archived from the original on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ “Texts for Common Prayer”. anglicanchurch.net. September 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ a b c “Anglicans Observe Ash Wednesday”. Anglican Communion News Service. 5 February 2008. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ “Ash Wednesday”. The Church of England. Archivedfrom the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February2018.

- ^ “Member Church – North India”. Anglican Communion. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ “Member Church – South India”. Anglican Communion. Archived from the original on 27 June 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ “Ash Wednesday”. Episcopal Church. 5 July 2011. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Sturdy, Rob (23 February 2017). “Ash Wednesday: An Anglican Tradition?”. The Ridley Institute. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ “Ash Wednesday”. Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ a b Bartlett, David L.; Taylor, Barbara Brown (12 October 2009). Feasting on the Word: Year C, Volume 2: Lent through Eastertide. Presbyterian Publishing Corporation. p. 22. ISBN 9781611641189. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Jethani, Skye (5 March 2014). “March 5, 2014 – Ash Wednesday” (PDF). Patchogue Church of the Nazarene. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ “Ash Wednesday Ideas”. Community of Christ. Archived from the original on 21 October 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ “Lectionary of the Ecclesia Gnostica”. gnosis.org. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ “First Day of Lent, Ash Wednesday”. The Evangelical Covenant Church of Canada. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Wagner, Abp. Wynn (6 February 2011). A Catechism of the Liberal Catholic Church (4th ed.). BookBaby. p. 53. ISBN 9781609849306. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ a b Cabie, Honor Blanco (14 February 2018). “Ash Wednesday ushers in time of remorse”. Manila Standard. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ “Askonsdag” (in Swedish). Church of Sweden. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Ahlgrim, Ryan (13 February 2018). “‘Remember that you are dust‘“. Mennonite World Review. Retrieved 14 February2018.

- ^ Harader, Joanna (18 February 2015). “Preparing to enter Lent – thoughts on Ash Wednesday”. Mennonite World Review. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ “Ash Wednesday”. The Methodist Church. 14 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ “Ash Wednesday 2018 Worship Resources”. Metropolitan Community Churches. Retrieved 14 February2018.

- ^ “Lent for Everyone: Matthew, Year A: A Daily Devotional”. Moravian Church in North America. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Moravian Women’s Association (March 2017). “Lent around the world” (PDF). The Moravian Church British Province.

- ^ Scanlon, Leslie (7 February 2005). “Ash Wednesday: What do Presbyterians do?”. The Presbyterian Outlook. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/events/day.dir.html/2018/2/14.html

- ^ Blain, Susan A. “Lent – Ash Wednesday”. United Church of Christ. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ Sleeth, Nancy (23 February 2017). “How do you observe Lent?”. The Wesleyan Church. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ “Written Answers. – Cigarette Smoking”. Dáil Éireann. 18 February 1997. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012.

- ^ Chronic long-term costs of COPD Archived 10 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Dr Jarlath Healy, Irish Medical Times, 2008

- ^ Ban on smoking in cars gets Minister’s supportArchived 11 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Alison Healy, The Irish Times, 2009

- ^ 20% of smokers light up around their children every day Archived 25 August 2010 at the Wayback MachineClaire O’Sullivan, Irish Examiner, 2006

- ^ The History of No Smoking Day Archived 30 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, No Smoking Day website

- ^ FAQ: When is No Smoking Day 2010? Archived 7 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, No Smoking Day website

Jonny Rosch with Gordon Edwards and Stuff – Wednesday, March 13th – Bogardus Mansion – NYC – 7PM

Jonny Rosch with Gordon Edwards and Stuff – Wednesday, March 13th – Bogardus Mansion – NYC – 7PM