Timothy Cratchit, called “Tiny Tim“, is a fictional character from the 1843 novella A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. He is a minor character, the youngest son of Bob Cratchit, and is seen only briefly, but serves as an important symbol of the consequences of the protagonist’s choices.

| Timothy “Tiny Tim” Cratchit | |

|---|---|

| A Christmas Carol character | |

Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim Cratchit as depicted in an illustration by Fred Barnard

|

|

| Created by | Charles Dickens |

| Portrayed by | See below |

| Information | |

| Nickname(s) | Tiny Tim |

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Bob (father) Mrs. Cratchit (named Emily in some adaptations)(mother) Martha Cratchit Belinda Cratchit Peter Cratchit Unnamed sister Unnamed brother (siblings) |

Contents

Character overviewEdit

When Ebenezer Scrooge is visited by the Ghost of Christmas Present he is shown just how ill the boy really is (the family cannot afford to properly treat him on the salary Scrooge pays Cratchit). When visited by the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, Scrooge sees that Tiny Tim has died. This, and several other visions, lead Scrooge to reform his ways. At the end of the story, Dickens makes it explicit that Tiny Tim does not die, and Scrooge becomes a “second father” to him.

In the story, Tiny Tim is known for the statement, “God bless us, every one!” which he offers as a blessing at Christmas dinner. Dickens repeats the phrase at the end of the story; this is symbolic of Scrooge’s change of heart.

As representative of the impoverishedEdit

Dickens often used his characters to demonstrate the disparity between social classes that existed in England during the Victorian era, and the hardships suffered at that time by the poor. These representative characters are typically children, presumably because children are most dependent upon others for survival, especially when they come from the lower social classes. Tiny Tim is among these characters, and is the most notable example in A Christmas Carol.

When the audience first meet Tiny Tim, he rests upon his father’s shoulder, suggesting that while the Cratchits love their boy dearly, his situation is nonetheless a burden on the family. Further representative of this burden is Tiny Tim’s crippled condition. That he is crippled evokes the financial issues that many poor families faced in 19th-century England. Although his spirit is robust, Tiny Tim’s life expectancy is questionable. His crutch and iron frame support his frail body—he “bore a little crutch, and had his limbs supported by an iron frame”, but more support is needed for Tim if he is to survive, as pointed out by the Ghost of Christmas Present in stave III: “I see a vacant seat in the poor chimney corner, and a crutch without an owner, carefully preserved. If these shadows remain unaltered by the future, the child will die.” These are a microcosm of the impoverished population: without support or charity, their family will be reduced.

The relationship between Scrooge and Tiny Tim is a condensed depiction of the relationship between two social classes: the wealthy and the impoverished. Tiny Tim plays a large part in Scrooge’s change. Tiny Tim’s fate is linked very closely to Scrooge’s fate, which tightens the connection that Dickens establishes between the two social classes. If Scrooge does not change his miserly ways, Tiny Tim is sure to die. Likewise, if the wealthy do not do their part to support the impoverished, the impoverished are sure to struggle. That Dickens framed this relationship with Christmas seems to suggest the immense need for decreasing the distance between English social strata. The proximity of the Christmas spirit to the issue of social strata lends a sense of community to Dickens’ message, urging the well-to-do upper class to consider the dependent poor, especially during the holiday, but year-round as well.

Character developmentEdit

In early drafts, the character’s name was “Little Fred”.[1] It has been claimed that the character is based on the son of a friend of Dickens who owned a cotton mill in Ardwick, Manchester.[2] However, Dickens had two younger brothers both with “Fred” in the name; one called Frederick and another named Alfred. Alfred died young.[1] Also, Dickens had a sister named Fanny who had a disabled son named Henry Burnett Jr.[3] Tiny Tim did not take his name from Fanny’s child, but the actual aspects of Tiny Tim’s character are taken from Henry Burnett Jr.[3][4]

Dickens tried other names such as “Tiny Mick” after “Little Fred” but eventually decided upon “Tiny Tim”.[1] After dropping the name “Little Fred,” Dickens instead named Scrooge’s nephew “Fred”.[1]

IllnessEdit

Dickens did not explicitly say what Tiny Tim’s illness was. However, renal tubular acidosis (type 1), which is a type of kidney failure causing the blood to become acidic, has been proposed as one possibility,[5] another being rickets (caused by a lack of vitamin D).[5] Either illness was treatable during Dickens’ lifetime, but fatal if not treated, thus following in line with the comment of the Ghost of Christmas Present that Tiny Tim would die “[i]f these shadows remain unaltered by the Future”.

Notable portrayalsEdit

The child actor Dennis Holmes played the role of Tiny Tim on Ronald Reagan‘s General Electric Theater in the 1957 episode “The Trail to Christmas”.[6]

The role of Tiny Tim has been performed (live action, voiced or animated) by, among others:

- Phillip Frost in the 1935 film Scrooge

- Terry Kilburn in the 1938 film A Christmas Carol

- Glyn Dearman in the 1951 film Scrooge

- Joan Gardner in the 1962 animated television film Mister Magoo’s Christmas Carol

- Richard Beaumont in the 1970 film Scrooge

- Timothy Chasin in the 1977 television film A Christmas Carol

- Mel Blanc (as Tweety Pie) in the 1979 animated short film Bugs Bunny’s Christmas Carol

- Dick Billingsly (as Morty Fieldmouse) in the 1983 animated film Mickey’s Christmas Carol

- Anthony Walters in the 1984 television film A Christmas Carol

- Mary Lou Retton in the 1988 film Scrooged[7]

- Jerry Nelson (as Robin the Frog) in the 1992 movie The Muppet Christmas Carol

- Don Messick (as Bamm-Bamm Rubble) in the 1994 television special, A Flintstones Christmas Carol

- Ben Tibber in the 1999 television film A Christmas Carol

- Jacob Collier in the 2004 TV movie A Christmas Carol: The Musical

- Ryan Ochoa in the 2009 film A Christmas Carol

ReferencesEdit

- ^ a b c d Leigh Cowan, Alison. “A 166-Year-Old Manuscript Reveals Its Secrets,” New York Times (December 24, 2009).

- ^ Seacock, Doug. “Charles Dickens—Writing from Life”. Egypt Cotton Times. Archived from the original on 2007-07-20. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

- ^ a b Perdue, David. David Perdue’s Charles Dickens Page, accessed December 3, 2012.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter (1990). Dickens. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 978-1-85619-000-8.

- ^ a b Lewis, Donald W. (1992). “What Was Wrong with Tiny Tim?”. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 146 (12): 1403–7. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1992.02160240013002. PMID 1340779. Lay summary – Time (December 28, 1992).

- ^ ““The Trail to Christmas” on General Electric Theater, December 15, 1957″. Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved November 25, 2012.

- ^ “Scrooged.” The Washington Post, 1988-11-25. Retrieved 2018-11-25.

External linksEdit

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- A Christmas Carol at Project Gutenberg

- [http://special.lib.gla.ac.uk/exhibns/month/dec1999.html A Christmas Carol – In Prose – A Ghost Story of Christmas)—Special Collections, University of Glasgow

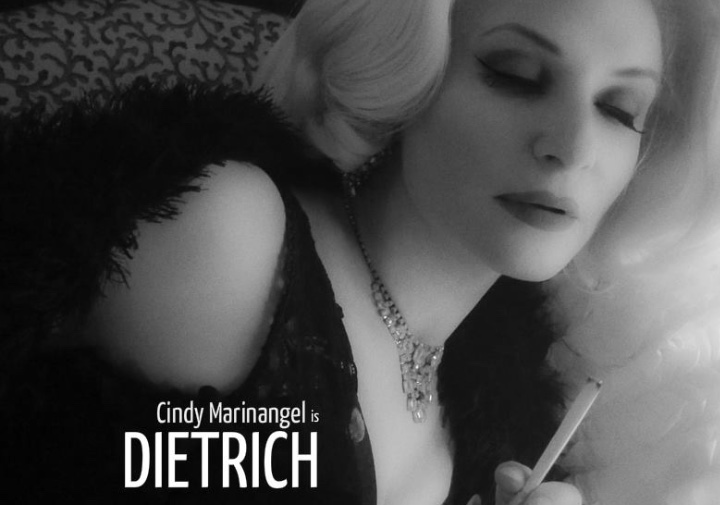

“Dietrich” will play Sunday, Jan. 6 at 3 p.m. and Monday, Jan. 7 at 7 p.m. The Triad,

“Dietrich” will play Sunday, Jan. 6 at 3 p.m. and Monday, Jan. 7 at 7 p.m. The Triad,